Much of this lack of information is probably due to the way that she died and the disrespect given to both inebriates and women who cohabited with men. But some of it was also due to Eliza’s partner George Clark’s own failings. He survived Eliza by only three months, dying from delirium tremons, a consequence of excessive alcohol intake. By the time Thomas Sunderland was attempting to fill in some of the blanks on Eliza’s death certificate George Clark was dead and the only information available was from the inquest into Eliza’s death, at which the likely inebriated George was the prime witness. Held at the Royal Hotel (now the Pinsent) in Reid Street on the 8th March 1854 (the day after Eliza’s death), the inquest heard from George Philips, a sailor then living in Wangaratta, that Eliza had been drinking for the fortnight he had known her. He also deposed that George Clark seemed kind to Eliza and that he had never seen Clark “ill use”, that is, be violent towards her. This was particularly important testimony as the circumstances of Eliza’s death were unusual with George Clark waking up next to her dead body. Clark deposed that Eliza had been complaining of illness for the seven months before her death, and despite drinking heavily for some time, had not taken drink on the day of her death. Clark, who was a sailor like Philips, had been living with Eliza for 18 months.

The inquest, conducted by coroner Dr William Augustus Dobbyn was short and incomplete. Dobbyn was new to Wangaratta and went on to have a long history as the local coroner and medical practitioner. He was, however, not always attentive to his duty and at times himself presented drunk to emergencies and births, and was involved in some less than savoury incidents involving preventable deaths. How much Dobbyn influenced this inquest is unknown. Certainly no other witnesses were called and the questioning of the two witnesses seems unusually sparse. Dobbyn did not carry out a post-mortem, or that part of the inquest has not survived, so it is impossible to say if Eliza had a disease caused by alcoholism or something else. Either way, the jurors were quick to determine, probably with Dobbyn’s recommendation, that “the deceased Eliza Armstrong died from the effects of liquor”. The jurors were: Dominick Farrell, James Britcheson, Henry Augustus Clarke, Benjamin Slater, James Fahey, George Gordon MacPherson, John Maloney, George Minson, Eben Ellingwood and William Byrne.

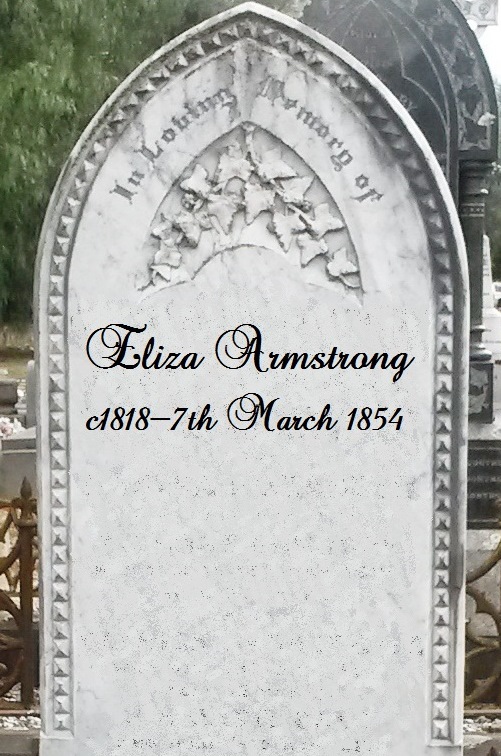

Eliza’s death certificate was completed more than four weeks after the event – on 11th April 1854. Her death date was incorrectly recorded as the 22nd February and no date of burial is mentioned. Records from Wangaratta cemetery for the 1850s have not survived, and Eliza’s death certificate only notes that she was buried at Wangaratta cemetery with George Clark as a witness. No local newspaper existed in 1854 with the Beechworth-based Ovens & Murray Advertiser commencing in 1855. Although Wangaratta was proclaimed a place where a Court of Petty Sessions could be held in March 1851, extant records begin only in 1858. If anyone can shed any light on who Eliza Armstrong was please contact me.

**I am indebted to Carmel Galvin who generously gave me ideas on how to illustrate a post about someone who left so little evidence of their life. Pop on over to Carmel’s blog to see the great ideas she has: http://librarycurrants.blogspot.com.au/

Such a sad story! But you’ve written it so well. I hope you do find more information about her life. Your illustrations are terrific and has made me rethink how I could illustrate some of my posts.

This post somehow snuck past me. But it is a good illustration of the newish adage that “Well behaved women seldom make history”. http://www.chicagonow.com/listing-beyond-forty/2015/07/who-said-well-behaved-women-seldom-make-history/ But it can be a similar story for men who lead a similarly unblemished life. Particularly if they don’t make their mark down at the Registrar’s Office getting married or having children. The 19th century and earlier was a world of semi-literacy, and we are lucky to have the records that we do. Where we are unlucky is when the name is so jolly ordinary/common. And what a shame many officials didn’t take their office (for which they were paid) terribly seriously. Like the egregious Dobbyn and Lucas in the above story, and other registrars who would record “No medical attendant”, if there was no doctor present at a birth, and ignore the attendance of a midwife, thus rendering her community service invisible. Even though it was a requirement of the system. And the carelessness of people! It beggars belief that an employer would not know the name of an employee when he suddenly died, and not able to identify someone he employed. Hence all the identities unknown in the inquest files. This became even worse in the killing fields of Europe in WW1 when soldiers were merely “Known unto God”, as they could not be identified. But now we know we carry our own story within us, in our very dna. Will it lead to another generation of grave-robbers? Still, you have to be able to identify the grave.

My only thought is – what if someone made enquiries for her in the newspaper columns? Maybe years later. In Sydney or Melbourne or elsewhere.

Thanks for your comments and insight Lenore. That’s a great suggestion to search for others making enquiries for Eliza after her death. I am sure I was fixated on finding information about her while she was alive.

Sadly there are too many Elizas in our history. Your illustrations especially the headstone add emphasis to your story.

There are too many Elizas, Jill and I’ll be talking about a few more of them in the near future. Thanks for dropping by. 🙂

It’s a bit sad really. It would be great to fill in even just a few details about her life.

Hi Lorraine, It is sad that people can live and die virtually un-noticed. Now I have realised I should have put Eliza’s potential birth year on her mock headstone as it would have looked a bit more personal. Thanks for dropping by. 🙂

A great summary of a sad life…I feel foe Eliza that her existence rated such little notice. Hopefully, with your research and maybe that of others, you will be able to give her the acknowledgement that all deserve.

Carmel is indeed a font of knowledge, great ideas for the illustrations.

Thanks Chris. I may just change Eliza’s mock headstone so it is more evident for visitors when she was born and hopefully it will ring bells with someone. Carmel’s images are wonderful! And her tip about photofunia.com will keep me from the housework for weeks! 🙂

I couldn’t resist…I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

http://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2017/06/friday-fossicking-16th-june-2017.html

Thank you, Chris

Thanks Chris!

Eliza certainly was a mystery Jen. You seem to have covered any avenue I would think of. Hopefully someone will suggest a new one. I was really impressed by your illustrations and had read about Carmel’s ideas but hadn’t yet gone to look. Thanks for the information.

Hi Kerryn, I hope I covered every avenue but then again I hope there is one I missed! Actually I didn’t check the court records for Eliza so there’s something I can still do. Carmel’s images are wonderful and they gave me the ability to do a post about someone for whom I had absolutely no illustration. Usually I wouldn’t attempt such a thing so it has broadened my thinking.