I’ve been reading early local inquests in an effort to solve a few minor but nonetheless interesting questions. My first question was about the location of Samuel Cheek’s Bridge. This existed in the 1860s and was not much more than a log across the One Mile Creek but it featured in at least two local events. I’ll do another post on this ‘bridge’ but reading a newspaper report of an inquest related to this spot, I found a wonderful description of how jurors for inquests were selected.

In July 1862 the Wangaratta correspondent for the Beechworth based Ovens and Murray Advertiser made the following complaint:

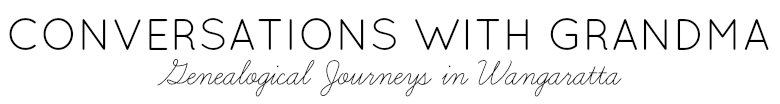

1863 map showing the route of a policeman seeking jurors, from the Police Office in the top left to 1/ the Royal Victoria hotel, 2/ the Royal (now the Pinsent) and 3/ the Commercial.

While on the subject of inquests, I beg to state that the system here of summoning jurymen is very annoying to several parties having business premises in Murphy-street especially, for when a jury is required, a ‘blue bottle’ is started to procure the same. He invariably starts from the Royal Victoria Hotel, takes a stroll as far as the Royal Hotel; and by the time he reaches the Commercial Hotel, Mr ‘Bobby’s’ arduous duty is accomplished in a circuit say, of 200 yards, and any unfortunate wight this worthy can see is nabbed, no matter how pressing his business.

Storekeepers, and all tradesmen living on ‘Bobby’s’ favorite track, are in for it; and if a stranger or two could be grabbed and kept in town for two or three days, it would make no difference to ‘ Bobby’ what expense he was put to so long as Mr ‘Bobby’s’ own turn was served. Just as Mr Bayly, the auctioneer, commenced selling by auction in large lots, on Wednesday, at Mr Leacy’s store, a gentleman in blue came to the sale room, where 50 people were assembled, and selected five of the principal purchasers during the sale to serve on the above inquest, but the Coroner kindly adjourned the inquest at the request of several parties from two till four o’clock, and but for this Mr Bayly might have shut up.

The term ‘blue bottle’ is an old English one, derived from rhyming slang for “bottle and glass” = arse, and of course blue was a reference to the colour of a policeman’s uniform. It may also be a reference to blue bottle flies who congregate around manure and the other detritus of life.

The ‘system’ of ‘summoning’ as described by the writer conjures up comedic scenes of men scuttling away when they saw a police officer approaching, particularly if they had heard of an untimely death. Those who were unfortunate enough to be in the middle of a business transaction or were visitors to the town were more likely to be ‘collared’. Publicans were relatively safe as they probably couldn’t leave their hotels during opening hours, but their staff and other businessmen were fair game. It is interesting that in the given example of an auction being interrupted, neither Michael Leacy whose items were being sold, nor the auctioneer Albert Charles Bayly were apparently selected. Men attending the auction were perhaps adjudged to have more time available and the auction was a perfect place to ‘select’ jurors as there were most likely several men in attendance. Did “Mr. Bobby” select men he knew had the ability to contribute to an inquest, or men he didn’t like and could choose to inconvenience? Or did he choose men who weren’t important and influential enough to make a complaint about the procedure, but were steady and reasonable men who didn’t have the type of connections to make a complaint? The prudence of police is also brought into question if they did seek jurors from inside hotels. We would now see that as unwise, but in the period in question a person was not considered drunk until they fell down and could not get up. Being tipsy was staggering when one walked.

Mounted policeman, sketch by Charles Lyall circa 1850s, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria. A foot policeman would not have carried a sword.

The correspondent went on:

In the Standard, of Wednesday, the Wangaratta correspondent of that paper, dolefully sympathises with a Mr C. Grover, an Oxley farmer, for being detained on the inquest on Margaret Donnelly for three days. I can not see how Mr C. Grover is entitled to more commiseration than Mr Thomas Church, an overseer at the Boughyards station, 18 miles from here, who suffered the same fate.

Surviving documentation for inquests held during the mid to late nineteenth century is relatively sparse so it is difficult to determine how they operated. Some of the simpler inquests appear to indicate that witnesses and jurors were assembled at the same time, and the inquiry itself was dealt with relatively quickly, with all witnesses giving evidence on the same day that a verdict was reached. But the above report suggests that this was not always the case. The inquest for the child named Margaret Donnelly mentioned in the above complaint was a longer one than usual as the likelihood of criminal charges being laid was evident from the beginning. However we can’t find out any more about the conduct of this inquest as the inquest file became part of the subsequent criminal investigation. I’d like to know if the jurors were held in the hotel in which the inquest was conducted, or were they free to go home or take a break and wander around town gossiping while witnesses were rounded up? Sadly newspapers fall silent on the conduct of the inquest and the fate of Margaret’s killer, and the culprit does not appear in prison records.

**Thank you to Lenore Frost who alerted me to the fact that the previous image I used in this post had been incorrectly catalogued and was not in fact of a policeman. You can see Lenore’s blog on Essendon, Flemington and the Keilor Plains here.