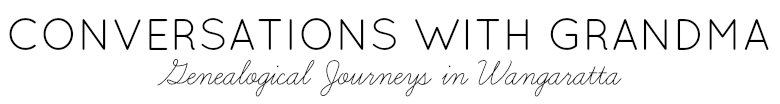

Ada Cross (nee Cambridge), courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Ada Cambridge was a well known, late 19th century novelist and poet. Born as Ada Cambridge in 1844 in Norfolk, England, she married the Reverend George Frederick Cross in Cambridgeshire in April 1870, and within five weeks the young couple had boarded a steamer bound for Victoria. You can read more about Ada’s literary career here and here. Such has been her renown that Ada and her work is still being researched today, most deeply by Margaret Bradstock. Ada’s first memoir was titled “Thirty Years In Australia”. Initially serialised by The Empire Review in 1901 and 1902, it was published in book form in 1903. Republished in 1989 and 2006, editor of the latter edition Margaret Bostock added place names where Ada had infuriatingly used only capital letters and dashes to identify people and places. So we now know that the first appointment of her husband George was to Wangaratta (1870-1871), the second to Yackandandah (1871-c1873), followed by Ballan, Learmonth, Beechworth (1885-1893) and retirement in Williamstown. The posts in this series do not seek to regurgitate any research already undertaken on Ada’s literary works, but to add background, colour, detail and personality to the section of her personal memoir that was set in Wangaratta and has hitherto gone somewhat unexplored.

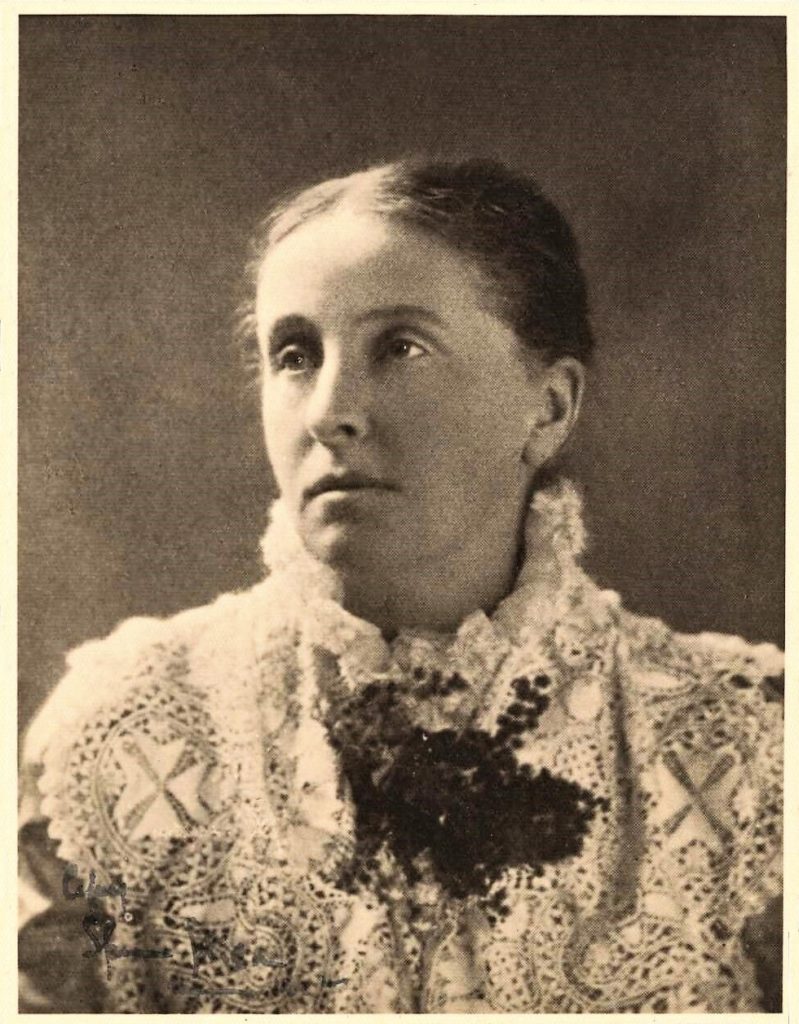

Bishop Charles Perry, courtesy of the National Library of Australia

When George and Ada landed in Melbourne in mid August 1870 they were accommodated and entertained by Bishop Charles Perry while George awaited an appointment. The couple did not have to wait long with Ada recording “On Saturday the 24th, the eighth day from our arrival, we turned our backs upon all this wild dissipation and our faces towards stern duty. We left Melbourne for the Bush.” In 1870 the only major train line from Melbourne travelled to Echuca. The north-eastern railway did not open until 1873. Reverend Cross and Ada travelled on the Echuca line, stopping for a few days to stay with the family of another Anglican clergyman at an undisclosed location. This was most likely at Kyneton with the family of William Chalmers (1833-1901), the wife of whom Ada described as “aged twenty-one and four years married”. Chalmers’ wife was indeed Henrietta (nee Rich) who he married in 1866 and Ada abbreviated her name to “Mrs C”.

Leaving the Chalmers household on the 31st August 1870, Ada and George took a circuitous rail route to Wangaratta to avoid coach travel as “The year of the great flood” was already making its reputation. Bridges and culverts had been washed away, and the coach-road was reported impassable for ladies. Men could wade and swim, assist to push the vehicle and extricate it from bogs …but the authorities in Melbourne advised my husband that it was too rough for me.” Leaving Kyneton on Wednesday afternoon the couple arrived in Echuca and boarded a small steamer on the Murray River. George was expected to take up his incumbency by the next Sunday but travel on the river was treacherous with “the debris of houses and bridges, trees, stacks, all sorts of things” threatening the vessel and slowing progress. At one stop along the Murray River, realising he was not going to arrive at his destination in time for the Sunday service, George hired a local man and his cart to take them overland for the final part of the journey. Here, Ada expressed her excitement at the adventure and the landscape that had seemed so alien before. Perched atop their belongings, drinking in the scenery she declared, “it was the morning of the day, of the season, of the Australian year, of our two lives; and I could never lose the memory of my sensations in that vernal hour. I can sniff now the delicious air, rain-washed to even more than its accustomed purity, the scents of gum and wattle, and fresh-springing grass, the atmosphere of untainted Nature and the free wilds.” Life beckoned and it was good.

The final part of the journey to Wangaratta did not however, go to plan. Rain set in and the horse struggled in the muddy conditions. Ada and George alighted from the cart in order to lighten the load on the horse, with Ada walking ahead. After hours walking in rain Ada realised she was lost as she could no longer hear the horse and cart owner behind her. Sitting down on a log she was serendipitously found at dusk by a local man on horseback who rode off, returning with a buggy and warm rugs. She was deposited at his homestead while her rescuer went back to find George, the cart owner and the horse which was by then stuck in a bog with only it’s head and neck showing. Everyone was rescued and Ada given a warm bath, clean borrowed clothes, food and a warm bed to sleep in. In the morning their un-named host drove them “some eight or nine miles“. Ada recollected “finally we dashed in style into the township and up to the parsonage-gate, where a venerable archdeacon was anxiously looking for the curate whom he had almost given up for lost.” We have no clues as to the identity of Ada and George’s rescuers, but from her description of the location they were probably residents of Killawarra.

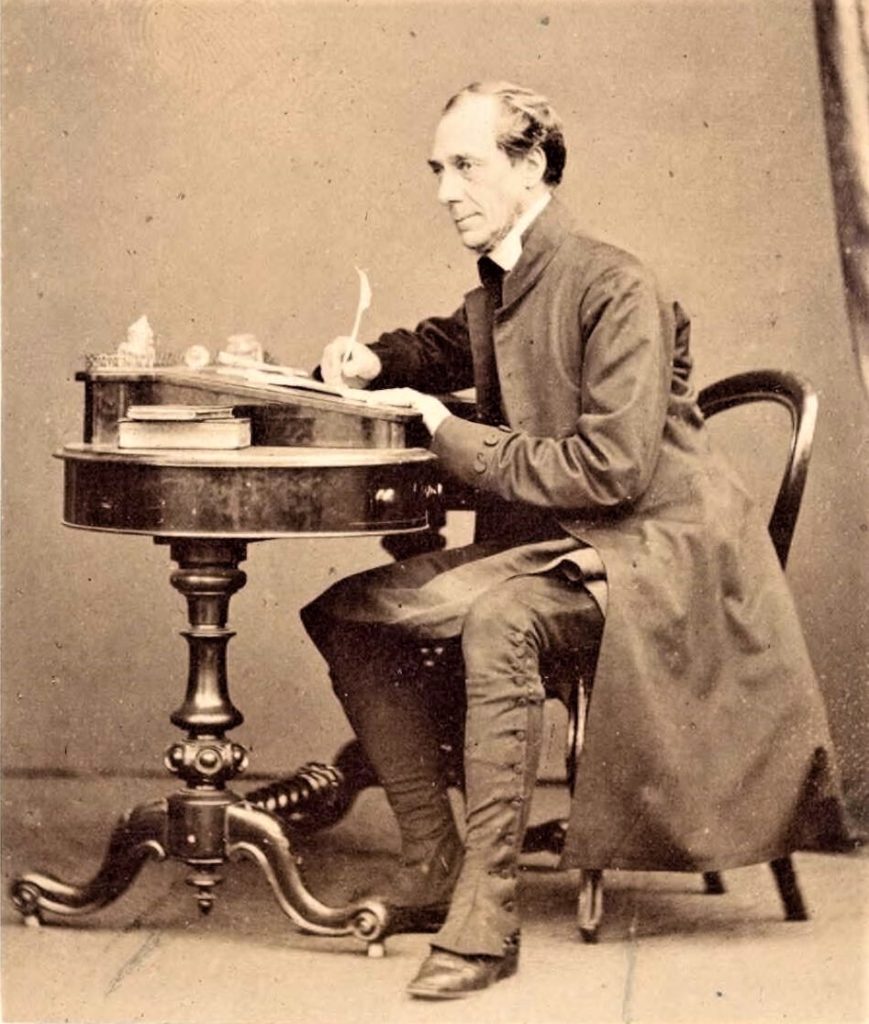

Trinity Church and parsonage (left), wood engraving, Ebenezer and David Syme, September 10th, 1872, Courtesy of State Library of Victoria

The Archdeacon at Wangaratta that Ada referred to was Joseph Kidger Tucker (1818-1895), father of Horace Finn Tucker (1849-1911) who during the depression of the 1890s promoted his Tucker Village Settlements. Tucker senior, had published two works on converting Indigneous people and the Chinese to Christianity in the 1860s. At Wangaratta, Ada and George lived in lodgings while waiting for more permanent accommodation to become available. Ada extolled the virtues of her surroundings. “Never had I known such air and sunshine, or such health to enjoy them…” Her only complaint with the landlady was her over generosity and imagination when it came to quinces. “At first they were a novel and welcome delicacy, but when we had had them at every meal for weeks – in jam, jelly, tart, pudding, and pie, with cream, with custard, with bread and butter, an inlaid in sandwich cake – we were so thoroughly sickened of them that neither of us has wanted to look at a quince since.”

And so Ada’s life in Wangaratta began. In Part 2 of this series we will gain some insight into Wangaratta society by examining the players in Ada’s social life and how they interacted with each other.

**All quotes from Ada Cambridge in this series of posts are from Thirty Years in Australia, available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b566133. This post refers to pages 23-33.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks