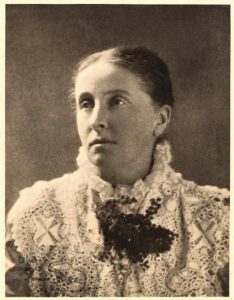

Ada Cross (nee Cambridge), National Library of Australia.

After doctors, bankers came next in social importance in Wangaratta according to Ada Cambridge’s memoir Thirty Years in Australia. She described them as “the backbone of country society“, remarking how important it was that “they should be popular with their constituents, as well as to man’s own interest to make life pleasant in a place where he may be settled for many years.” She also observed that they were “handsomely housed, and live in the best Bush-town style“.

Later she went on: In W-, in 1870-1, the bank people were of very good quality – one household in particular, the heads of which belonged to two substantial colonial families of high repute (which they still enjoy)…

There were several bank branches in Wangaratta in the early 1870s. You can read more about some early banks here. But the couple that Ada Cambridge was most enarmoured with must have been Arthur Jennings Smith and his wife Mary Alsop. Mary was the daughter of John Alsop who had held the prestigious position of Inspector of Stamps at the Melbourne Post Office before his untimely death in South Australia in 1860. Alsop’s position was possibly second only to an inspector at the mint, as stamps were often used as informal currency and were relatively expensive.

Arthur Jennings Smith had arrived in the colony of Port Phillip in the late 1830s and eventually settled at Cheshunt, which was named for his birthplace in Hertfordshire, England. Smith took part in many early events of Wangaratta and was deeply entwined with early players in the town’s history. He was the manager of the Bank of New South Wales in Wangaratta in the late 1860s, the ill-fated Oriental Bank in late 1870, then back to the Bank of New South Wales, and later managed the Commercial Bank of Australia in 1875, and according to his obituary was also associated with the Bank of Australasia. It was noted that Smith had been “mainly instrumental in getting the North-Eastern [railway] line constructed, and was at the time banquetted for his successful endeavor.” He was also elected a member of the Wangaratta School District Board of Advice in 1873, and was President of Wangaratta Building Society in 1874. His obituary also stated that Smith “was a gentleman of considerable talent, and had a sound acquaintance with a great variety of subjects, his unusual comprehensive knowledge being frequently displayed in letters to the Melbourne papers.“

Arthur Jennings Smith was also a witness to the Will of Alfred Currie Wills whom we met in Part 2 of this series on Ada Cambridge, so he was part of Ada’s wider social circle. He was also in business in the Victoria Brewery with Daniel Hugh Evans, J.P., (and Godfrey Downes Carter). Evans was the friend of Alfred Currie Wills, who was called on when Wills first became ill. Smith and Evans had many connections, including being involved in formation of the The Wangaratta Building and Lands Improvement Loan Benefit Society in September 1871, with Smith as the President, and Evans on the committee. My ancestor William Henry Clark was also heavily tied up in business deals with Daniel Hugh Evans, including being partners in the Victorian Steam Flour Mills in the early 1860s. Clark, Evans and Smith were all squatters at the time, and all were enthusiastic supporters of the same start up mining companies, and all were involved in almost every early institution including the Wangaratta Committee of the North-Eastern Railway League.

Smith’s religious pedigree would have been particularly agreeable to Ada Cambridge and her husband George Cross as his father was the Reverend J. Jennings Smith, reportedly a former Queen’s Chaplain, or Honorary Chaplain to the Queen. Arthur Jennings Smith himself had a long and complex connection to the Wangaratta Anglican church. He was a Commissioner appointed by Chancellor of the Church of England Diocese of Melbourne to investigate the behaviour of Reverend Caleb Booth in late 1866 in which Booth broke a dog’s leg during a church service at Trinity Church.

Clark memorial window in Holy Trinity Cathedral, copyright author’s collection

Smith was also appointed trustee of the land upon which Trinity Church stood in November 1871, following the death of William Henry Clark and the resignation of Police Magistrate Robert William Shadforth and Edward Harman Macartney. He was an executor of William Henry Clark’s Will, but strangely, declined to take up the role when Clark died in April 1871. Clark’s probate was a large and complex affair so perhaps the task was overwhelming for an already busy man. Alternately, Clark and Smith may have fallen out over the widely publicised behaviour of Caleb Booth and his subsequent punishment which certainly split the congregation. This scenario may seem unlikely in context as the pair had known each other since at least 1849 (and most likely since the late 1830s when they were both early settlers), when they were involved in the Adelaide Smelting Company. Launched in January 1849 and operating under a patent, the original agreement had seven directors of which one was William Henry Clark, and Arthur Jennings Smith was one of the trustees. Clark was also heavily involved in businesses with Daniel Hugh Evans and the three men often appeared on committees together.

Clark, aka The Father of Wangaratta, donated a large portion of land to the original Trinity Church (situated behind the current Cathedral) in the 1850s, and a double window in Holy Trinity Cathedral is dedicated to Clark and his wife Elizabeth (nee Harris), yet Clark was never acknowledged in the social scene that Smith and Ada Cambridge inhabited. He was self made, without any worthy pedigree and possibly social talents, and was an old and ailing man by the time Ada Cambridge arrived in Wangaratta, so perhaps she did not even meet him. There was certainly no comment in her published memoir when Clark died.

Ada had a wonderful time in the company of Mary Smith, wife of Arthur Jennings Smith: “The lady here was a charming woman and hostess, famous in local circles for her pleasant parties, for which I frequently needed the evening dresses that I had supposed would be superfluous Indeed, … I was gayer in that first year of “missionary” life than I had ever been in England“.

Sadly, none of Mary Smith’s social gatherings were reported in the Beechworth-based and digitised Ovens & Murray Advertiser. The local Wangaratta Dispatch may reveal more about Mary on a personal level.

See the next instalment of Ada’s memoirs here.

**All quotes from Ada Cambridge in this series of posts are from Thirty Years in Australia, available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b566133. This post referes to pages 39-40.