Ada Cambridge, undated, National Library of Australia

After Ada Cambridge wrote about the people who became her closest friends during her short residence in Wangaratta, she took to observing the community and comparing it to life in England.

And as for the cottage people – the marked thing about them was that they were not “the poor”. There was none with whom a clergyman or his wife could safely take the liberties so customary at home. When a sister-in-law … started to make herself useful by teaching the parishoners their duty along traditional lines and by bestowing doles of old clothes and kitchen scraps upon them, she got some tremendous surprises – ‘insolence” that simply staggered her.

This was the egalitarian society that Ada had commented on previously. Like all Australian towns in this era, Wangaratta was a frontier town. Built from the ground up, by people who stepped up and stepped forward, the society had no infrastructure or community organisations to fall back on, unless the people created them. Everything was created from scratch by the residents who could ill afford any snobbery or strict adherence to rank. If the common people didn’t co-operate and get things done, then there was little progression. Community members saw no need to give undue deference to religious representatives, and certainly did not consider themselves poor or in need of charity as they may have done in England. Even Ada’s term “cottage people” was rarely used in Australia. The reversal of roles between England and Australia was not lost on Ada.

No, what they loved was to bring us little presents of new-laid eggs or poultry or what not, and to charge us less than they charged the laity … The whole attitude of parishes and lay people in the country towards their spiritual pastors is benevolent to a degree. The parental spirit, tolerant, indulgent, making allowances (in more senses than one), is here on their side. The schools teach their children for half fees; the doctors doctor them for no fees at all; …

It appears that Ada, or at least some religious colleagues, had difficulty accepting the special treatment given to religious representatives. However, she did not acknowledge that these feelings were likely the same as those of people who had been insulted by offers of charity from her own quarter.

And as long as they accept this role of lame dog that needs helping over the stile, so long will there be that tinge of contempt and patronage which embitters these favours to some of us who receive them.

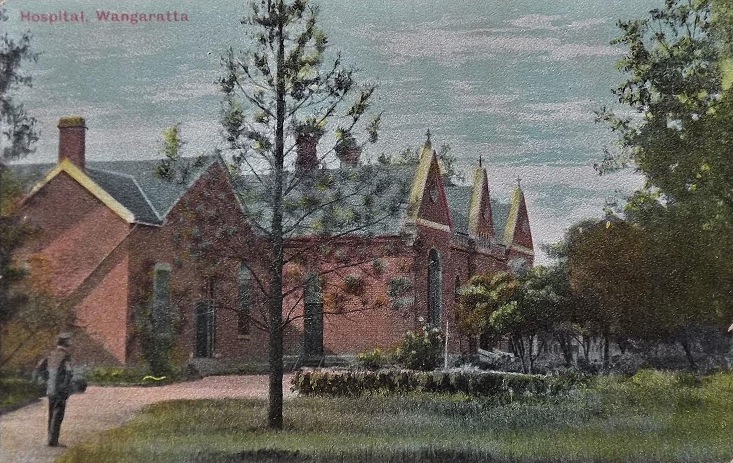

Community based benevolence was certainly on the rise in Wangaratta during this period. Ada may have witnessed the laying of the foundation stone for Wangaratta’s own hospital in January 1871, and a Benevolent Asylum was envisaged so that residents did not have to travel to Beechworth for care. A Ladies Benevolent Society had also been active since at least 1869. Reverend Tucker was on the committee of the hospital so Ada’s husband George Cross may well have been involved as well.

Original Wangaratta Hospital built 1871, but image dates from circa early 1900s, author’s collection

Ada sounds like she felt at home in Wangaratta, and in the brand new society that Australia was.

Coming straight from our dignified Cathedral life, with its high and mighty Church-and-State traditions, into this democratic Salem-Chapel-like atmosphere, we still found nothing to disagree with us … Pure loving -kindness and open-armed hospitality to strangers surrounded us on all sides but one, and the unexpected welcome went to our young hearts.

Continuing on this series with Part 8 we will next discuss Ada and George’s “single disappointment” that has long mystified scholars.

**All quotes from Ada Cambridge in this series of posts are from Thirty Years in Australia, available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b566133. This post refers to pages 42-43.