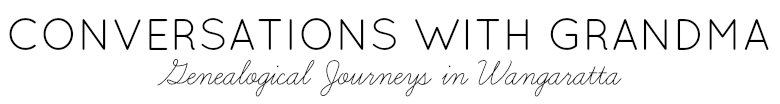

Ada Cross (nee Cambridge), National Library of Australia.

As we saw in Part 6 and 7 of this study, life in Wangaratta agreed very well with Ada Cambridge. However in her memoir she hinted at a disappointment that wounded deeply, but which she could not elaborate on.

… we still found nothing to disagree with us – only one circumstance excepted, for which neither the country nor the parish was to blame. Pure loving-kindness and open-armed hospitality to strangers surrounded us on all sides but one … The single disappointment came from a quarter whence it was least expected. But, as to that, bygones may be bygones at this time of day. I shall not tell tales.

Students of Ada Cambridge have commented on how little she gave away about this disappointment. Certainly newspapers of the time did not specifically point to any drama involving the Cross family. Her only hint is that “neither the country nor the parish was to blame“. Does this suggest an issue higher up in the hierarchy of the church?

When Ada and George Cross arrived in Victoria they were immediately subjected to the political machinations of the Church of England and the highly unpopular Bishop Charles Perry of Melbourne. In January 1870 the Ovens & Murray Advertiser had published an editorial that was not at all complementary to Bishop Perry.

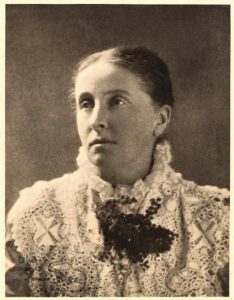

Bishop Perry, c1860-1864, unknown photographer, State Library of Victoria

Bishop Perry is like Cardinal Richelieu — he will not reign, save with absolute power. He must have the Church under his thumb, or he will resign his bishopric. It is not with him a question of right or wrong, of justice or in justice, it is simply a matter of carrying out his own opinions at all risks. From time to time, the ordinary Christian public has been startled by the arbitrary acts of the head of the Victorian Church of England. …The Bishop has certain notions of his own upon the proper method of public worship, and any clergyman who does not subscribe to those views either receives the Episcopal cold shoulder, or has the light of the Episcopal countenance withdrawn from him. For a long time the Church has suffered in silence, but the last act of oppression has raised a storm of indignant expostulation on all sides…

Our Bishop admits no one to his councils. He has no tiresome body of advising cardinals, no council whose counsellings may move his mighty mind. The Church Assembly is dumb, for if a man will not agree, neither shall he eat, and a recalcitrant curate is easily disposed of … It is high time that this arbitrary, old gentleman was brought to a sense of his position. Zeal may become tyranny, and firmness obstinacy. There is a growing feeling of repugnance to the narrow-minded spirit evinced by Bishop Perry and his peculiar people, the ultimate effect of which cannot but be to injure that Church over which he so rigorously presides.

The idea mooted some time back of forming this portion of the colony into an archdeaconry has been carried into effect, and the office conferred, on Dr Tucker,- who has been appointed Archdeacon of Beechworth and Sale, likewise taking the incumbency of Wangaratta. At a meeting of the committee held at Trinity Church, Wangaratta, on Monday evening, letters were read from the Bishop of Melbourne and the registrar of the diocese, to the effect that the appointment of Dr Tucker had been confirmed, and that that gentleman might be expected to enter on his duties during next month. Dissatisfaction was expressed at the archdeaconry being styled that of Beechworth and Sale, and it was determined to communicate with the bishop on the subject.

By the time George and Ada arrived in Wangaratta, Archdeacon Joseph Kidger Tucker was well settled in his position. However, serious discontent with Bishop Perry simmered and rose again by mid April 1871 when he held a visitation in Beechworth for the first time. George Cross attended. Reported in the Ovens & Murray Advertiser, Bishop Perry’s speech began with a very lengthy and rambling account of his own authority, and his instructions on a very narrow interpretation of dogma including exactly how the scripture should be taught and a host of other views including the use of music within the church. He followed with a further lengthy refrain about obedience to his authority and a plea for clergy to “refrain from forming parties for the propagation of their several opinions.” Perhaps Perry’s threats to use his power on non-conforming (in his view) clergymen in the Wangaratta diocese by refusing ordination was one thing that cut to the heart of Ada and George Cross.

A bishop is invested by the church with the power of rejecting, according to his own sole judgement, any candidate for ordination. … But no court of law can compel him to ordain a man whom he deems for any reason whatever to be unfit for the ministry. … Against these evils the only security of the church lies in the character of the bishop himself for diligence of investigation, sound and unbiassed judgment, and a strict conscientiousness … in examining candidates for ordination. … I cannot conscientiously ordain, or admit to the ministry in this diocese, any one who does not give me satisfactory assurance, that he heartily approves, and will strictly adhere to, the doctrine and directions of the church in these particulars.

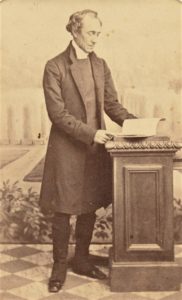

Trinity church old building, A J Evans, State Library of Victoria. This is the building that George and Ada Cross would have been familiar with. The building on the right is the first stage (chancel end) of the stone Holy Trinity Cathedral. The older building was demolished as the next stage of the cathedral was undertaken.

While the possibility of remaining in the Wangaratta district AND George having his own parish initially seemed remote under Bishop Perry, Ada’s specific mentions of Bishop Perry in her memoir do not give any sense of animosity towards him. Recalling when they first arrived in Melbourne, Ada mentioned that “whether as host or guest, the first Bishop of Melbourne was always perfect …”. Later in her memoir Ada noted that “the regular path of promotion to a Melbourne parish is to be elected by the Board of Nominators, and that that path was virtually closed to us … because we were so distant and little known.” She mentioned a second option that the Cross’ did not consider. This was to be appointed directly by a Bishop to a parish that Ada described as “lame ducks of parishes” by virtue of being too small to have their own nominators, or not being qualified to have a nominator due to their churches still being in debt. Ada had ambition for George’s career and no doubt for her own life, but they seemed hamstrung on a number of levels. It seems likely that the lack of a personal appointment for George was one source of frustration for Ada, even if it was not her “single disappointment”.

Later Ada gave greater weight to the contention that George’s professional position was the source of her worries.

We did not really settle down in W—. Life there was difficult and worrying on the professional side, and with every passing week we longed more to extricate ourselves from a position that we had seen at the beginning to be without promise of comfort or success. But on the social, the secular, side, we had nothing to complain of.

I’ll leave it up to students of the Anglican church to decide if Ada’s gripe was with the systems in place within the church, or Bishop Perry, or had something to do with Archdeacon Joseph Kidger Tucker.

In Part 9 of this series, we will look at Ada and George’s time at ‘Como’, the residence of their late friend Alfred Currie Wills, whom we met in Part 2.

**All quotes from Ada Cambridge in this series of posts are from Thirty Years in Australia, available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b566133. This post refers to pages 44, 67 and 255 of the book (267 of the scan).