Ada Cross (Cambridge), National Library of Australia

Continuing on a study of the personal memoir of novelist Ada Cambridge titled Thirty Years in Australia we come to the young couple’s housing in Wangaratta.

When Ada Cambridge and her husband George Cross arrived in Wangaratta they had been married for several months, but had not had the opportunity to make a home together. The town was booming and independent accommodation scarce. When the young couple finally had the opportunity to move out of the home of Archdeacon Tucker, Ada wrote, “The absorbing joy, to start with, was the making of the first home. The town was so well filled that it was a difficult matter to find a house: we took the first possible one that offered, after waiting several weeks for it.”

A large railway station now stands … upon the site. Walking about the Bush in the vicinity, we used to find here and there in the ground small pegs which we were informed were the surveyors’ marks for the line. … The spot was quite on the outskirts of the township, and we passed from our premises straight into the Bush behind the house, which faced some open waste ground, analogous to an English common of unusual size, which divided us from streets and church.

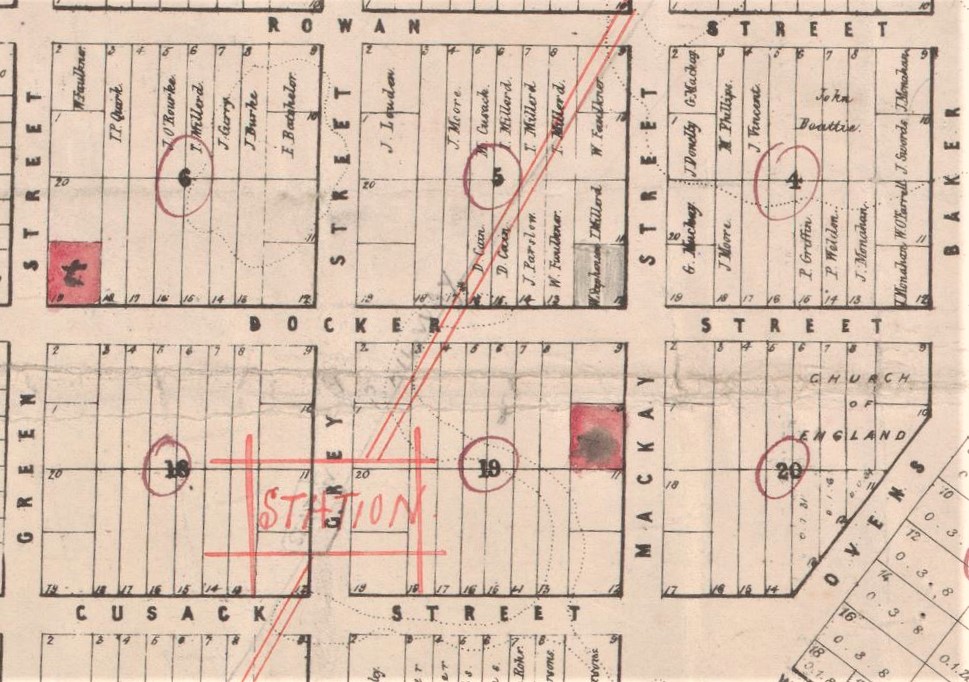

The description of Ada and George’s first home situates it on Section 18 or 19 of Wangaratta township. If the house was truly on the exact location of the railway station building that would locate it on Section 19. However, most of Section 19 was not sold until 1872, whereas the station end of Section 18 was sold in 1859, making it far more likely to have had a house on it. It is a shame that Ada did not name the owner of her property as this would have enabled the exact location of her home to be identified.

Map of Wangaratta showing Section 18 where Ada possibly lived, and the Church of England on the right in Section 20.

House do I call it! Three tiny rooms, opening one into the other, the first into the outer air, a lean-to at the back, and a detached kitchen – that was all. We paid one pound a week for it, which certainly was an excessive rent for such a place.

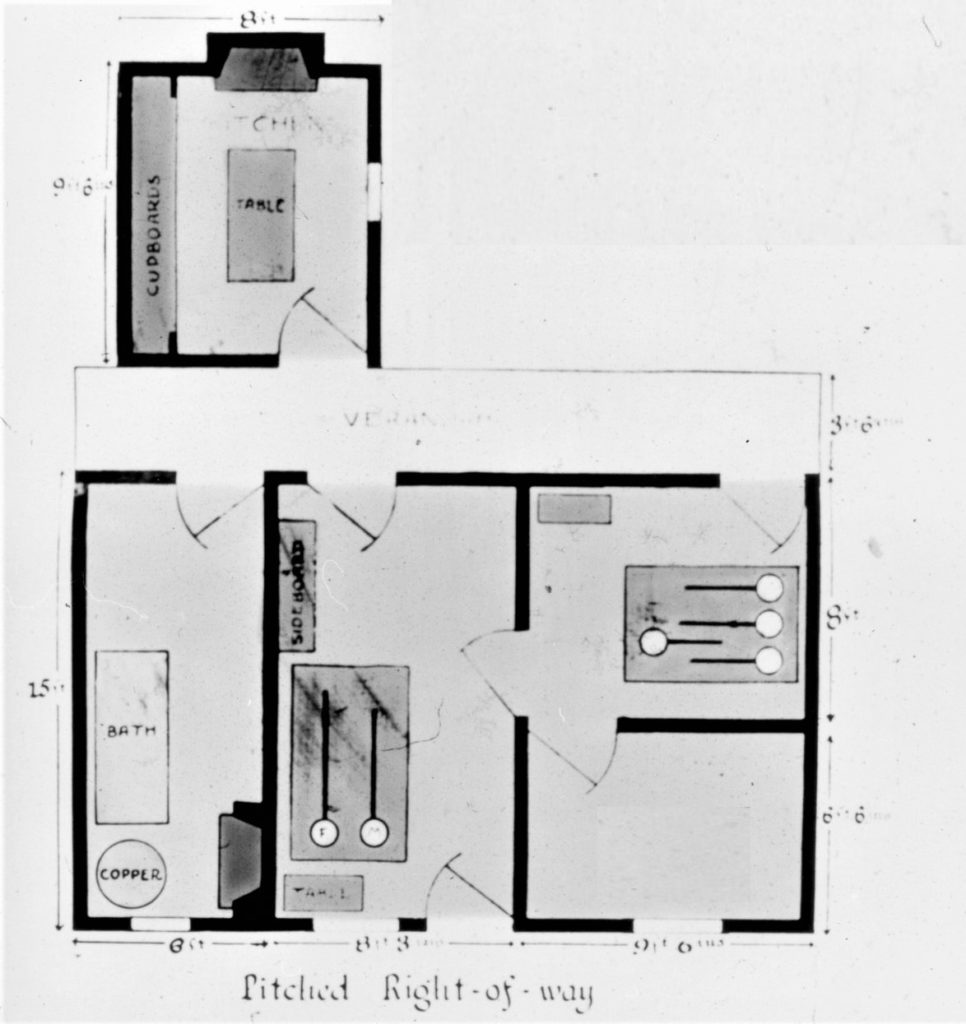

Plan of a typical three room worker’s cottage of the era.

Ada’s first marital home was modest by her standards but sounds like a typical timber worker’s cottage of the era. The following is a plan of a three-roomed cottage with a rear lean-to that was most often a combined laundry and bathroom, with a separate kitchen, both accessed from outside the house via an adjoining verandah. The rooms show the way a family lived in them, with four children sharing one bed.

Wages in the colony were also a shock to Ada. A shortage of labour meant that occupations could command much higher wages than back home in England. Of course this was to some extent caused by the higher cost of living with many necessities having to be brought from Melbourne by wagon. It is a shame that Ada did not give any further clues as to whom the young Irish servant was.

Excessive also were the wages we gave our first servant, an amiable but inefficient Irish girl–fifteen shillings a week.

Ada’s description of her home and the efforts she put in to making it not only comfortable, but respectable and presentable to her new friends took up a lot of her time and ingenuity. A curate’s income must have been meagre indeed, and it seems that there was no stipend available to either Ada or George from back home. She describes making all her furniture coverings, mat and curtains and was proud of the fact that she made all her own clothes and that of her children for many years. Ada’s ingenuity knew little bounds. She also turned her hand to furniture making with George making the frames out of hardwood and Ada upholstering them. Her feather mattresses that were brought out from England were turned into pillows, and cushions which covered, like charity, all the sins of amateur workmanship in our springless couches.

Ada’s mention of the lack of a street at the front of her homes suggests an unmade road, or a road that was merely marked on maps, but was not any kind of reality to the residents. This sits well with the house being on Section 18, with lots in Section 19 not being put up for sale yet. The room of our cottage that had the front door in it was the sitting-room… Here we dined in full view of the street–had there been one–when summer evenings gave light enough; our doctor and his wife, pulling up their horses before the house, could see for themselves whether we were at the end of our meal or in the middle; I would go out with an offer of pudding or coffee sometimes, but as a rule I left everything and flew for hat and gloves. Here again, the affection that Ada felt for Dr James Hester, “our doctor”, whom we met in Part 3, is very apparent.

The room at the other end was our bedroom. The little cubicle between combined dressing-room and study. There was not space to swing a cat in any of them, had we wanted to swing a cat. But after all, humble as it was, it was a sweet little place when we had fixed it up. Bishop and Mrs Perry, paying us their first call, were enthusiastic about it. They had been making a long tour from country parsonage to country parsonage, which, notwithstanding the benevolence of parishioners, are as a rule struggling homes, “shabby genteel,” in their appointments; and this bright, simple, tidy (though I say it that shouldn’t) little toy dwelling was, to use their own word, an “oasis” amongst them. One truth that I have learned from my manifold domestic vicissitudes is that you can make a nice home out of anything, if you choose to try. You do not really want all the things that you are brought up to think you want. Sometimes it is even a relief to be without them.

I do enjoy these minute observations of Ada Cambridge’s life in Wangaratta. Her whimsical little house and her pride in the simple accomplishments of good housekeeping and home decorating in such trying circumstances are heartwarming – though always remembering that as poor as they were, they had help in the home.