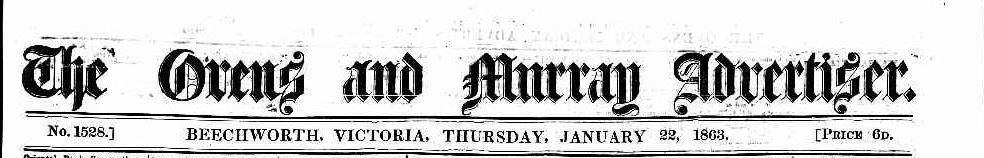

In January 1863 the Beechworth based Ovens & Murray Advertiser (O&MA) published a fascinating and at times hilarious account of Wangaratta. The report is important as the office of the Wangaratta Dispatch (later Despatch) was destroyed by fire sometime in the 20th century. I remember my grandfather telling me about the fire and the loss that is represented for the early history of the town. I have been unable to establish when that fire occurred but I suspect it was in the early 1970s. The first edition of the Dispatch was produced by John Rowan on the 21st March 1862, yet the State Library of Victoria holds only editions from 1875 when Angus McKay was the proprietor, possibly due to that loss by fire. An alternative explanation for the lack of early editions of the newspaper is that Legal Deposit in Victoria did not begin until 1882 and the Dispatch may not have been prudent enough to keep an archive of its own publication before that date.

1863 was also an important year for Wangaratta. The Municipal District of Wangaratta was declared in June with the first elections held, and later that year the new Municipal Act of 1863 created the Borough of Wangaratta. The article by the O&MA is long and quite detailed. As a very early look at the town and its institutions it is worth dissecting over several posts.

Wangaratta, though not one of the largest towns of Victoria, is one of the most ancient, having been founded in the past ages of New South Wales domination, long prior to the great Australian gold discoveries, and the consequent rush of population, civilisation, and universal suffrage. This town, situate on the banks of the Ovens and King Rivers, 160 miles from Melbourne, lies upon the trunk line of road between Melbourne and Sydney, and is surrounded by several agricultural districts, the principal of which are those of Estcourt, or Docker’s Plains, Oxley, Tarrawingee, and North and South Wangaratta. Upon these agricultural communities, the trade of Wangaratta principally depends, alike supplying their wants through its numerous stores, and converting their produce by its steam mills, &c., into merchandize available for the markets of Beechworth, the Jamieson, and Lachlan goldfields, and other places more or less distant.

This survey of the town seems normal enough (so far) but as you read on, bear in mind that the article may have been prompted by an event. My sense is that there was strong inter-town rivalry happening between Beechworth and Wangaratta and I suspect this article may have been ‘retaliation’ for a similar article about Beechworth published by the infant Dispatch.

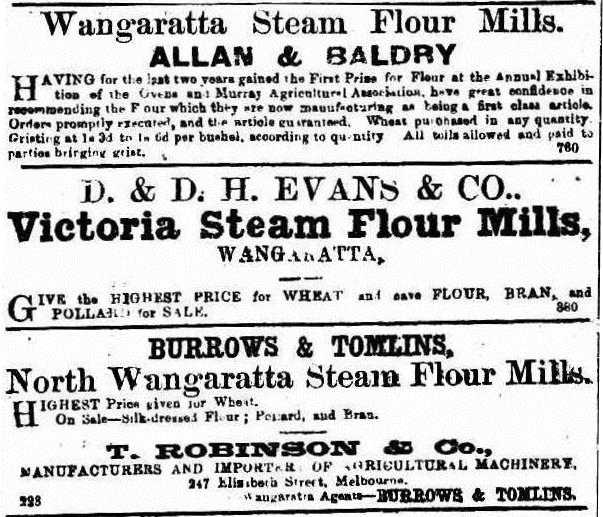

Wangaratta possesses three steam flour mills, the two larger of which Messrs Dale, Allan, and Co., and. Messrs Evans and Co., contribute largely to the substantiality of its appearance. The former, erected by Messrs Mackay and Reid about six years ago at a cost of £4000, is a very fine brick building. The latter, built by Mr Wm. Clark (the oldest inhabitant), and the late Mr John Evans, of Whitfield, contains machinery for working four pair of stones, and is second to none in the colony. Of course the flour trade is the principal branch, although almost every line of business, from fiddling to preaching, not omitting poteen-making [illicitly distilled whiskey], finds an exponent who carries it on, on a larger or smaller scale.

This advertisement from the O&MA on 2nd May 1863 shows the business of flour milling was a serious one. All three mills vied for business, making sure they used the same large size advertisement whilst also attempting to set themselves apart from the competition. William Allan (1830-1903) was the first partner. . David Whittaker stated that Allan, a Scottish flour miller helped build this first mill for Mackay & Reid in early 1857, later taking over the lease. Charles Baldry (c1829-1883) started out in John Foord’s flour mill at Wahgunyah before coming to Wangaratta and then moving on to Mansfield. The business of Allan & Baldry was still being referred to in the press in 1865. The Mr Mackay who built the Wangaratta Steam Flour Mill was Dr George Edward Mackay of Whorouly station who died in 1867. The mill was consequently sold in 1868 to Messrs. Graham and Wilson of Beechworth and Oxley, for £2000. Mackay’s business partner Reid may have been Dr. David Reid who took up Carraragarmungee station in 1838, although some sources suggest it was his brother John Reid. There is a family connection to this mill as the bricklayer was former convict Christopher Cook who married Ellen Considine, a sister of my direct ancestor Margaret Considine. Christopher was known for his wonderful bricklaying … and his sly grog selling.

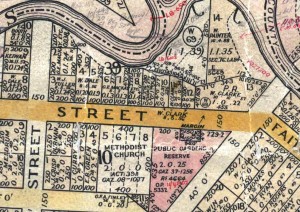

Wangaratta township 1857. Allan’s Mill is shown in the middle. It is located on the main thoroughfare from the south, and the corner of Murphy Street which became the centre of the business district. Image: NLA

It seems likely that this mill was a horse drawn mill. Judy Bassett and Edna Harman’s wonderful Wangaratta: Old Tales and Tours locates Mackay and Reid’s steam mill in Templeton Street opposite the Radio 3NE building but slightly closer to Ovens Street. This mill would have drawn water from the Ovens River whilst Allan’s mill on the map drew water from the King River. The issue becomes more complicated as Bassett and Harman locate Clark’s Victoria Steam Mills on the very corner where Allan’s mill is marked. As Whittaker concurs with this location it appears that Allan may have moved his operation to Mackay and Reid’s mill and then passed the King River location to William Clark who built the Victoria Steam Flour Mill in partnership with Evans.

The map above complicates the issue of the location of the mills. Radio 3NE that Edna Harman used as a reference point is located on Lot 7 at the back of the Methodist Church after that allotment was subdivided. Across the road to the left (as described by Harman) Lots 10, 11, 12 and 13 were owned by William Henry Clark so how could Mackay & Reid’s Wangaratta Steam Flour Mill be there? Lot 13 is the location of Clark’s Sydney Hotel, formerly the Hope Inn so Lots 10, 11, and 12 would have had to have been the location of any mill. On the other hand, Harman may have been correct about Mackay and Reid’s Wangaratta Mill being on that side of the street, but not been quite correct about the location. George Mackay actually owned Lots 6, 7, and 8 and Lots 4 and 5 were owned by William Dale, the miller mentioned in the newspaper report as being in partnership with William Allan running Mackay & Reid’s Wangaratta Steam Flour Mills in January 1863.

The Victoria Mill run by D & D.H. Evans in 1863 is the mill I am most interested due to its connection with William Henry Clark. His partner in building and running this mill in the early days was John Evans. The connection between Clark and the Evans family was particularly strong. When John Evans died in January 1862 Clark was one of the guarantors for his intestate estate. Evans died prematurely at the age of 57 after he accidentally shot himself in the side near the heart and the injury caused severe dropsy, or oedema. Evans’ obituary in the O&MA noted “that he was a man of an energetic and enterprising spirit; and … some few years since, he erected one of the most powerful steam flour mills in the neighbourhood. Mr Clarke [sic] has always predisposed to liberality towards [him].” Evans was also a squatter like Clark. He had taken up the Whitefield (later Whitfield) run in July 1853 after Clark had held the run since 1845. The team of Evans’ men running the Victoria Steam Flour Mills has me somewhat perplexed. The “D” Evans is most likely David Evans, the eldest son of John, who was granted probate to his father’s estate.

The “D.H.” Evans is most likely Daniel Hugh Evans. This man is most annoying to research from a family history perspective. Not only was he referred to only as “D. H. Evans” in most newspaper reports, his name appears to have been Daniel, yet he signed his name clearly as David on the birth certificate of his son Alfred Llewellyn in 1868 and various sources use different first christian names for him on the rare occasions when it is mentioned. It really sounds like his friends called him “D. H.” and possibly few knew his real name. When D.H. registered the birth of his son in June 1869 his occupation was recorded as “master miller”. Evans had married Rachel Edwards in 1852 in Bassaleg, Monmouthshire and arrived in Wangaratta soon after. A Justice of the Peace and a Licensing Magistrate he was clearly a man of some standing. By March 1862 the slightly differently named Victorian Steam Flour Mill was being advertised with proprietors “D. & D. H. Evans (late Clark & Evans)“, so we know that Clark had an interest in the mill until that time. Despite the advertisements running in their own papers news reporters were lax in their spelling, constantly recording wheat prices from “Clarke & Evans“. In every document he signed Clark was consistent with the spelling of his name as Clark (without an e) and today, some historical organisations in the region incorrectly record his name with an E despite holding artifacts sourced from the family bearing the name Clark. Very early maps record the name correctly but sloppy copying in maps from the 1860s have lead to the use of this spelling to this day.

I have always assumed that D.H. was the Evans that Clark was in the flour milling business with but looking at the advertisements it is not clear which Evans Clark sold out to as the Evans in partnership with Clark is not identified. I also haven’t worked out the connection between D.H. Evans and John Evans – if there is one. D. H. Evans was also one of the guarantors for John Evans’ probate so there is a good chance that there a genetic relationship between the two Evans’, although he may merely have been acting as a friend, as William Clark was. John’s death was not registered and the only useful information from his probate is that his wife’s name was Charlotte and she was illiterate. His sons were named David, John and Evan Evans. Great! That doesn’t help narrow the field at all! And to complicate matters, John’s first wife, and mother of his children was Elinor/Eleanor EVANS! Daniel Hugh Evans was born in Anglesey, Wales in 1830 to William John Evans and Jane Edwards. He was 25 years younger than John Evans so seems more likely to have been a nephew of John. No matter what the connection was between the two Evans men, there was a strong business link with William Henry Clark, “the father of Wangaratta”.

I believe Daniel Hugh Evans was initially a tutor for John Evans’ children.

Wasn’t a master miller per se, as had to be talked into offering advice on putting the flour mill back onto a ‘good footing’. Was very learned so people, including Clarke and the Bank Manager, assumed he was good at business – in 1860s some of the farmers still couldn’t read and write but were successful nevertheless.

Clarke went referee for him to secure a loan to buy into the flour mill. Ended up defaulting on £13000 pound loan to Bank NSW. Owed Clark’s estate £1500