I haven’t followed up with my Trove Tuesday posts using the description of Wangaratta that was published in the Ovens & Murray Advertiser (O&MA) in January 1863 for quite a while. Now that I am back on board, we will follow on from Part 5.

On entering Wangaratta from the northward, the Ovens Bridge toll-house divides the traveller’s attention with the Bank of New South Wales, which, standing on the high bank of the river, looks like the antitype of one of the famed castles of the Rhine.

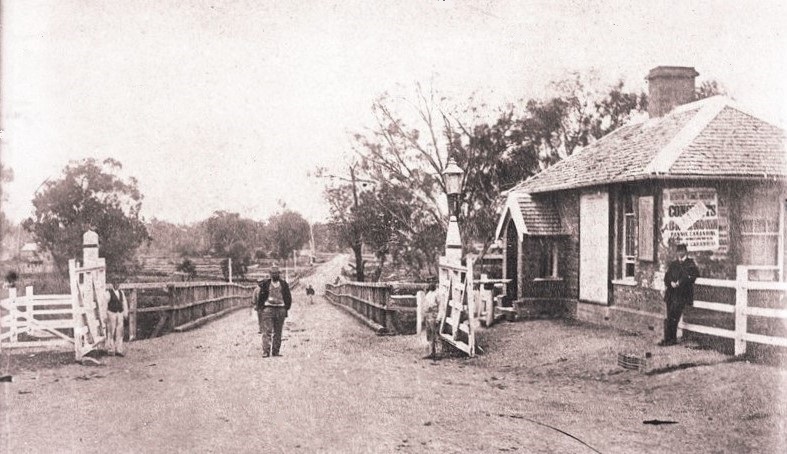

The toll bridge on the Ovens River was a scene of many newsworthy incidents and deserves a post in it’s own right. However, a brief description is warranted here. Tenders were called for the erection of the bridge over the ana branch of the Ovens River in October 1854 and tenders for the erection of the toll house in February 1855. The role of toll keeper was also contracted out. This was however, the second toll bridge, the first being leased to Joseph Griffith from 10th March 1853 to 31st December 1853, for the huge sum of £1,013. Clearly there was a lot of money to be made from collecting bridge tolls. The only surviving images of the second and main toll bridge are from the southern side of the river looking north with the background of river flats.

Second toll bridge looking north, circa 1863. The man on the far right looks like a postal worker, the man standing next to the gate on the right looks like he is wearing a policeman’s cap, while the man in the centre of the road looks like he was asserting his position and may have been employed by P. Hanna to collect the tolls. The two story building in the background on the far left was Meldrum’s Wangaratta Hotel.

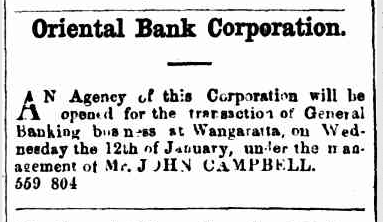

The rise in the bridge from roughly north to south makes it easy to imagine how the Oriental Bank on the eastern side of Murphy St could rise up and look so substantial to the visitor who compared it with a castle. The building was probably the first substantial building travellers from the north saw. As the writer observed, the Oriental Bank was a short-lived venture, opening in Wangaratta on the 12th January 1859. It’s arrival was heralded as a sign of the prosperity of the town but the bank seemed to just disappear, with no announcement about the closure of the Wangaratta branch. It is a shame that the occupant of the former Oriental Bank building was not mentioned in the 1863 article.

The Oriental Bank Corporation, and the Bank of New South Wales, simultaneously established branches at Wangaratta, about two years since, but after six months’ competition, finding the commercial cherry would not afford a bite apiece, the Oriental shut up, and left the field to their opponents, who, doubtless, reap the reward they anticipated.Adjacent to the Bank, is the National School house, lately rebuilt by the Local Committee from public subscriptions, aided by the late National Board. The National School was established by Sir Francis Murphy, Speaker of the House of Assembly, and other residents in the neighborhood, about eleven years ago, and has since been conducted with great success by careful masters, under the supervision of a Local Board, four of whom, Messrs Ryley, Clark, Dobbyn, and Cusack, have acted from its beginning.

The school building that this writer saw in 1863 was not the current two-story brick edifice but two newly erected brick class rooms that had replaced a rather shabby and small original rectangular timber building. For further information on the early years of the school see Dawn Floyd’s book: A History Of The State Primary School No. 643, Chisholm Street, Wangaratta 1850 – 2000.

The long serving local school board members mentioned here were Francis Ryley, the town surveyor; William Henry Clark, my ancestor; Dr William Augustus Dobbyn; and Michael Cusack, one time hotel owner, butcher, and a friend and business associate of William Henry Clark. The same men, again and again, were involved in the creation and support of local institutions in the young town. That Clark, Dobbyn and Cusack were long term friends and assisted each other in their personal lives and with the institutions they were involved in, is without question. Francis Ryley was also a committed local man from at least 1854 until 1865 when he resigned as town surveyor and returned to England, by which time Michael Cusack had also passed away.

Do you have any information about the bridge builders? I have a record saying that my great great grand father Henry Crock was involved, however I also have seen documents that say it was a CRONK not CROCK along with Robert Menzies who built it. Thanks. Liz Crock

Hi Liz and thanks for dropping by,

I do have some info on the original bridge but am not at the point of publishing it yet.

I have info that Henry Crock was recorded as a carpenter in 1859, and later as a sawmiller. Do you have anything earlier that situates him in Wang?

Your Henry Crock may well have helped build the bridge but it was often only the contractor who was mentioned in government records as winning the tender. As a sawmiller Henry may have supplied the timber for it.

What documents do you have about his role?

Kind regards,

Jenny

Hi Jenny, sorry I never saw this reply until now, when I have resumed searching for this information. I have quite a few documents about Henry Crock but as far as I know so far, he arrived in 1856 AFTER this bridge was built, though it is also possible that he came to Australia twice and was actually here in the early 1850s but I have no proof of that yet. He lived in Wangaratta at least from 1856-1879 then went to WA and had a sawmill there. I checked the Public Records Office for the tender documents and it said Menzies and Cronk, which still could be him as he didn’t write and was French-speaking (from Canada).

Hi Liz,

I do have some updated info on Henry. He signed a petition at Wangaratta to make the Ovens River navigable in January 1858. He gave his occupation as a carpenter and he did sign his name then.

In 1874 he was the contractor supplying timber for the new railway at Wang and in December 1874 he was a sawyer at Dockendorff’s saw mills.

All that fits neatly within your time frame. If I find him any earlier I’ll let you know. 🙂

Jen