Wangaratta Fire Brigade had it’s origins in a “Hook and Ladder Brigade” formed in 1872. This was rather late for the organisation of a co-ordinated fire fighting effort, considering that the settlement was over 30 years old. It wasn’t that fire was unknown in the town. On the contrary, fire was the largest destroyer of the town landscape for decades. James Henry Brougham Spearing was a victim of fire who brought the issue to the fore in Wangaratta in early 1872. Spearing had been the honorary secretary of a Hook and Ladder Brigade in Beechworth since 1866, but by 1872 that organisation languished and it’s equipment left to rot. At this time the Ovens and Murray Advertiser lamented that neither Wangaratta, Beechworth, Stanley, Bright or Yackandandah had any organised form of fire fighting.

Advertisement for Spearing’s Council Club Hotel and Royal Argyle Rooms, Ovens & Murray Advertiser, 12 February 1870, p. 1.

In the 1870s Spearing was the licensee (and possibly owner) of the Council Club Hotel and the Royal Argyle Rooms (also known as the Argyle Rooms) in Murphy Street, Wangaratta. The Argyle Rooms was a concert hall attached to the hotel. During a celebration for St Patrick’s Day in 1872, revellers in the Argyle Rooms had to flee as fire took hold in the large premises of Hugh Cavanagh, located next door. Cavanagh’s building, housing a retail and wholesale grocery, and provision, produce and drapery stores, was totally destroyed with insurance estimated at £3,400. At one point it was feared that John Grant’s furniture warehouse to the right of Cavanagh’s would be lost, along with George Chandler’s provision and grocery store and Spearing’s Council Club Hotel. The outcome was much better with no buildings other than Cavanagh’s lost, but the Argyle Rooms received “a severe scorching”. The damage wasn’t just confined to fire or water, however. The response to the fire by amateur onlookers was characterised by “more zeal than discretion”. Much damage was also done to the hotel by ‘excited’ (read drunken) party goers who ripped doors off their hinges, and broke windows and furniture, while other items were stolen in the mayhem. Running into burning or threatened buildings and saving items was the norm during this period but this report suggests more was afoot, and Sub-Inspector Montford and Senior Constable Cudden could do little to control what seems to have been rioters taking advantage of the chaos caused by the fire.

Less than two months after the fire Spearing chaired a meeting at his Argyle Rooms, “to take into consideration the desirability of forming a hook and ladder company for Wangaratta.” Spearing informed the meeting that the Council had determined to give the hook and Iadder company a truck which they had had made, together with buckets, ropes, etc. The company that it was proposed to form would be one that would be very simple in its constitution. A hook and ladder company was all that was required Wangaratta – a regular fire brigade not being necessary. The duties the company would have to fulfil would be simple. They would have to understand using the hook, ascending the ladder, and throwing water upon buildings. They were willing to take active men who were above 18 years of age. Those who joined would have to make themselves acquainted with the natural water resources of the place, so that if they had to turn out they would know where to obtain water on the darkest night. They would have to understand how to pour water on a building without injuring property. Recently when Dr. [William Harte] Miller’s chimney caught fire injury was done to property through those present not knowing how to put the fire out. They wished athletic persons to join the brigade rather than those who followed sedentary occupations. He trusted that when the company was formed that they would be able to purchase the apparatus which the Borough Council was prepared to hand over to them. He believed the cost would be about some £50 or £100. If they got together from 10 to 20 men, that would form a very good foundation for a hook and ladder company. Some 21 persons joined the brigade, and the following officers and committee were chosen:- Messrs Spearing, Coutts, W [William] Meldrum (of the Scandinavian Brewery), C H. Harris (secretary), Champ (treasurer), Fitzpatrick, Sharland, Lunt, and J. Johnson. The meeting adjourned until Friday, 17th.inst… when a captain and two lieutenants for the brigade are to be elected.

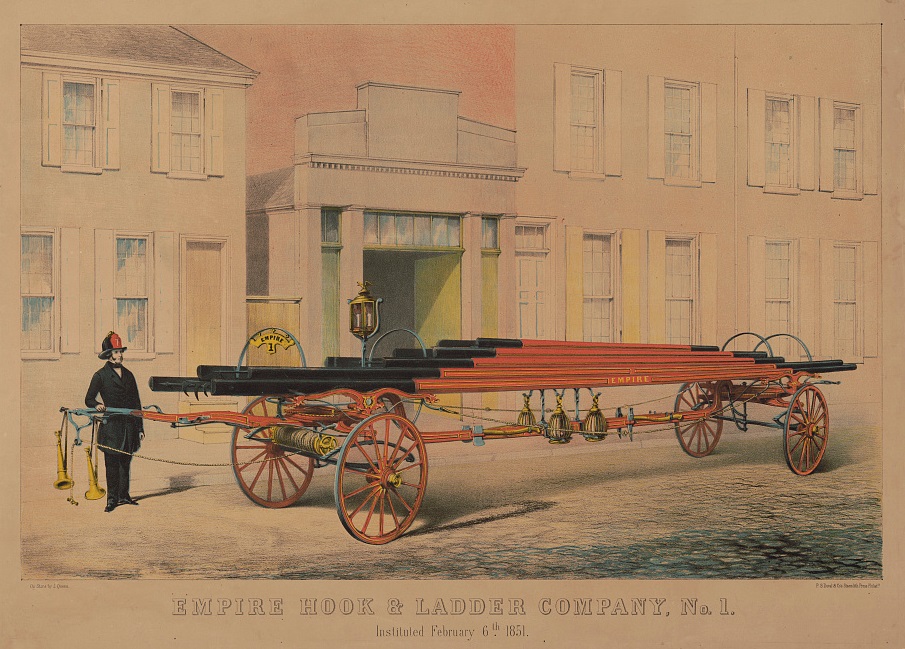

Below is an example of an early American hook and ladder cart. The image is of a very ornate and undoubtedly expensive version. The Wangaratta version was likely to be far more austere. The cart could be manouvered by hand from either end, allowing placement of the extendable ladder on buildings near the fire. The method of extinguishing fires was primitive and in many cases futile, particularly due to the lack of reticulated water. Firemen had to climb the ladder and using a rope, haul up buckets of water drawn from the river or other nearby water source, and throw them on to the fire. Of course this meant that fires could only be fought on the perimeter due to the heat, and for the most part, wetting down adjoining buildings to prevent them catching alight was the best anyone could hope for.

Thanks for the interesting article, Jenny. I wonder if any hook and ladder companies had any successes? It’s a bit of a desperate effort, hauling buckets up ladders!

I’d also like to know what the difference was between a hook and ladder brigade and a full fire brigade considering the latter was not considered warranted in 1872. Surely wiping out a major department store worth $3400 warranted the highest effort and the best equipment. I suspect that a full fire brigade involved a tank and some paid employees. I know some insurance companies had fire brigades of their own but I imagine this didn’t extend to towns, although I have read that they financially supported some brigades in large towns, leading to poor decision making in deciding which buildings to try to save.

A fire brigade would have a tank of water and a pump, and the pump would be manned by bystanders, largely, who would be enticed to assist by the handing out of tokens which could be redeemed for beer at some local pub. The early wagons were pulled by men rather than horses (who could keep a team of horses on standby?) so they didn’t go far from base – though most towns were probably small. Insurance companies maintained fire brigades for those buildings displaying that insurance company’s shield. If you didn’t have a shield, or the right shield, they would stand by and let it burn to the ground. A history of the Melbourne Fire Brigade says that insurance brigades would rush to the scene, but only the brigade associated with the insurer would fight the fire, and the other brigades would try and hamper the one fighting the fire!

How difficult a time they had in fighting fires, not that it is or was, ever easy, but I would think that we have a far greater chance of saving homes and buildings now than then. Thanks for this, I learnt quite a bit.

Thanks for dropping by Chris. It was appalling wasn’t it? No wonder whole streetscapes were wiped out.