Ada Cross (Cambridge), courtesy National Library of Australia.

Continuing on a study of the personal memoir of novelist Ada Cambridge titled Thirty Years in Australia we come to the first description of her social life in Wangaratta.

The town of W-, where we spent the first year of our Australian year, was a typical country-town of the better class, and at that period very lively and prosperous. … We found a highly civilised society. The Police Magistrate at the head of it – always a P.M. was at the head in those days in the country-towns big enough to have one, and not only by virtue of his official standing, but by every right of personal character and culture, as a rule – was a (to me) surprisingly well bred as well as kindly gentleman: and his wife was as nice as he. They gave bright evening-parties, at which he played the flute with a delicate skill, and he read largely and liked to talk of what he read; also he was an exemplary husband and father. In the group of pleasant households, his was one of the most serenely pleasant, and so we felt it deeply when one morning, a few months after our arrival, the news of his sudden death was brought to us.

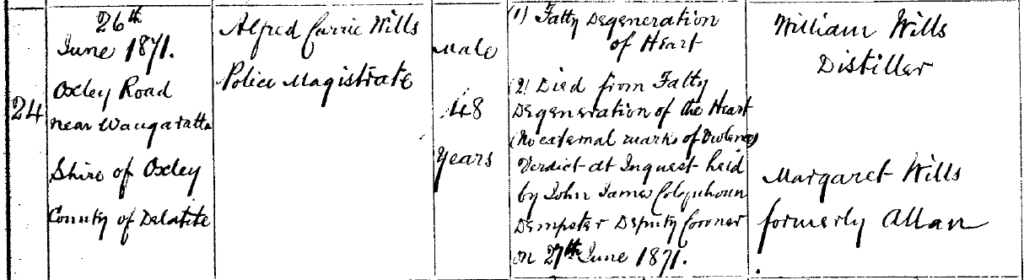

The Police Magistrate in this case was Alfred Currie Wills. Aged only 48 when he died on 26 June 1871 at his residence ‘Como’, the inquest found that he suffered from heart disease. The community was indeed as shocked as Ada. The initial article in the Ovens & Murray Advertiser said:

The report of the funeral of “this lamented gentleman” reflected the respect in which he was held. Ada Cambridge’s husband George Cross assisted the officiating Archdeacon Joseph Kidger Tucker.

Twenty-six vehicles, thirty horsemen, and fully one hundred and fifty persons in all, accompanied the hearse to the Episcopalian part of the cemetery, where the funeral service was performed in a most impressive manner by the Venerable Archdeacon Tucker, and the Rev Mr Cross. The procession was then re-formed, and on its return march its numbers both of vehicles and pedestrians were considerably increased. Business was quite suspended in Wangaratta, and all the stores were shut. Many persons attended from Bright, Beechworth, and El Dorado, and in fact from all parts of these districts.

Part death certificate of Alfred Currie Wills, Registry of Victorian Births, Deaths & Marriages 1871/7511

Wills was certainly a well-loved character. Eleven years before his death the Dargo correspondent to The Argus remarked, “The Government have a warden at Omeo, Mr. Alfred Currie Wills, an intelligent well-educated gentleman, and one who, when I was in that part of the country, was very much respected and liked by the miners.”

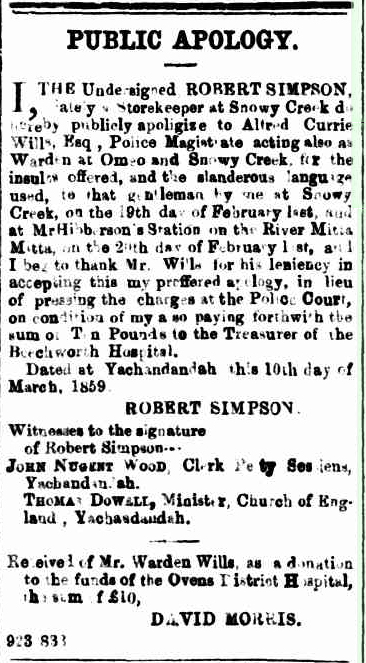

Simpson’s apology to Wills, Ovens & Murray Advertiser, 15 March 2019, p 2.

Wills was also an ingenious character. In March 1859 he extracted an extensive and grovelling apology from Robert Simpson. Printed in the Ovens & Murray Advertiser, Simpson admitted to publicly insulting Wills and using slanderous language on two occasions. He went on, “I beg to thank Mr. Wills for his leniency in accepting this my proffered apology, in lieu of pressing the charges at the Police Court, on condition of my also paying forthwith the sum of Ten Pounds to the Treasurer of the Beechworth Hospital.” David Morris, gave a published receipt for the funds, and the entire apology and signature of Simpson was witnessed by John Nugent Wood, the Clerk of Petty Sessions at Yackandandah, and Thomas Dowell, the Church of England minister at Yackandandah. The humiliation of Simpson was complete.

Ada Cambridge continued her memoir with an account of the death of Wills.

He had risen that morning apparently in his usual health, and was in his dressing-room, making his toilet and chatting with his wife through the open door between them – she with a baby a week or so old – when she heard him fall; he did not answer her call to know what was the matter, and when she went to see she found him dead upon the floor. The catastrophe left her with six little ones to provide for, and next to nothing to do it with. The good husband and father, taken without warning in his prime (of unsuspected heart disease), had begun to make provisions for the rainy day, but not completed the task.

Accounts given of the death of Wills at the subsequent inquest differ a little to Ada’s account. Arthur had a severe pain in his chest and Dr Hutchinson had been sent for. He assessed Wills and left to obtain medicine. At the same time one of the Wills’ daughters rushed to tell his friend Daniel Hugh Evans (friend and business partner of my ancestor William Henry Clark). When both Dr Hutchinson and Evans arrived at the house Wills was dead. Ada was probably recounting the events before Dr Hutchinson returned. She was correct about the children of Arthur and his wife Emma (nee Ring). They had daughters Florence Victoria (b1861 and at almost ten years old was probably the messenger sent to Evans), Theresa Knight (b 1863), Linda Marion or Mary (b 1865, a twin, the other daughter being stillborn), Margaret or Marjorie Allan (b 1867), Mary Lavinia (b 1869), and Alfred Currie jnr, born on the 12th July 1871 only 14 days before the death of his father.

Wills furniture sale, Ovens & Murray Advertiser, 22 July 1871, p. 2

As Ada Cambridge suggested, Wills did not leave much in the way of an estate. His major asset was a £1,000 life insurance policy, but his other assets of £275 consisted only of household effects, horses, a piano and a buggy. He had several debts, including one of £252 secured upon the life insurance policy. If the life insurance policy was paid out Emma would have been left with around £500 in cash plus her household goods. It is not clear why, but less than a month after the death of Alfred, Emma was reduced to selling off her household goods.**

However, with pupils and boarders and what not, she made a splendid fight of it. The baby son did not long survive his father, but the five daughters grew up to testify to her good mothering and to reward her for it. They are now good mothers in their turn, sharing her society between them.

Ada’s memoir is correct about the death of the only Wills son. Alfred Currie jnr passed away on the 5th April 1872, just before he turned 10 months old. A petition for a grant to the family was raised by the Mayor of Beechworth and acknowledged by the Chief Secretary’s Office in August 1871 but nothing is known about the outcome. Ada also suggested that Emma remained in Wangaratta, or at least in contact with Ada for a short time while she attempted to support herself. Emma was certainly still in Wangaratta in December 1876 when she sued William Wheeler over a £200 loan she had given him in late 1871. The deal was complicated by the fact that family friend Daniel Hugh Evans had been the intermediary and Wheeler claimed not to have known the loan came from Emma, stating that “Evans’ transactions and mine were rather complicated.” Emma won the case and that is the last we see of her in Wangaratta.

Emma and Alfred’s eldest daughter Florence married in Melbourne in 1883, as did other daughters in the next decade. Did Emma move to Melbourne? Ada’s comment that Emma’s daughters were “sharing her society between them” suggests that in later years Emma lived with either of her daughters. We next find Emma on the 1910 federal electoral roll living in Main Street, Stawell. Her daughter Margaret or Marjorie lived in Stawell with her doctor husband John Raymond Fox from at least 1903. Here, in early May 1912 Emma passed away and was buried in the Stawell cemetery, far away from her beloved husband and only son.

Alfred Currie Wills senior was buried in the Wangaratta cemetery but there is no record of any other family member being interred with him, and the exact plot out of a group of three graves is not recorded. He also has no surviving headstone. Cemetery records at this time were very poor and while Alfred is recorded in the Church of England group of plots numbered 306, his infant son is recorded as being in the group of three graves numbered 362, also without a headstone, and his surname transcribed as Wells. It is likely that the two are interred in the same grave but records have not survived to confirm at which location.

You can read more about Ada in Part 3 here.

**All quotes from Ada Cambridge in this series of posts are from Thirty Years in Australia, available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b566133. This post refers to pages 37-39.

** Alfred Currie Wills, probate file, Public Record Office of Victoria, VPRS 28/ P2 unit 3, item 9/125