By guest blogger Rod Martin

Wangaratta Agricultural High School students, December 1909, by J E B Archibald, Albury Council Museum and Social History Collection ARM 84.114. August 2024 – Thanks to John Mahony who pointed out that Julius Schilling, the teacher, may be the man seated far left with the moustache.

A question about the 1909 photograph shown above led to an unlikely coincidence as a blogger attempted to discover the real story behind it. The Albury Library and the State Library of New South Wales had both captioned it as being a picture of students from Albury High School on an excursion in Mt Morgan, with SLNSW adding that it was Mt Morgan in Queensland. However, it was quickly discovered that that institution did not open until 1920, so the picture had to be of students from another school. On further investigation, Jenny Coates discovered that an ‘agricultural high school’ existed in Wangaratta in 1909 and had field trips/excursions for its students in that year. Was the ‘A.H.S’ actually that school? If so, what was the excursion and where was the photo taken?

Jenny’s queries were sent to fellow blogger Lenore Frost (Empire Called and I Answered), who then Googled ‘Victorian agricultural high schools’ and accessed a thesis on the topic, written by myself – a contributor to Lenore’s blog! It really is a small world!

It is also a coincidence that, for five of my teenage years, I lived in Myrtleford and thus had some knowledge of the north-eastern district. When Lenore passed Jenny’s queries on to me, I was quickly able to discount some of her theories about the excursion, to confirm the status and the nature of the Wangaratta school, and to suggest that the photo was taken at Mt. Morgan, near Glenrowan.* [Note from Jenny: Mt Morgan has since been re-named Mt Glenrowan. It was the site of bushranger Dan Morgan’s lookout]. Subsequent research by Jenny led to the discovery of an account of the excursion published in the Benalla Standard on 24 December 1909. It was an inaugural break-up picnic for the school, founded in April that year. The picnic was conducted on 18 December. The photo shows the group of teachers and students after they had climbed to the top of Mt. Morgan. The headmaster, Mr. J. F. Schilling, was a part of the group.

The agricultural high schools, the first two of which were established in Sale and Warrnambool in 1907, were, after the establishment of Melbourne Continuation (later High) School in 1905, the first high schools in regional Victoria. A need for state involvement in post-primary education had been established by the Fink Royal Commission on Technical Education, conducted in 1899. Responding to criticism of the state’s educational system, the need for financial restraint after the depression of the1890s and the strength of the private schools lobby in the parliament, the report recommended technically-oriented post-primary schools that would in no way interfere with the existing secondary or public schools, or encroach upon the province of secondary education.

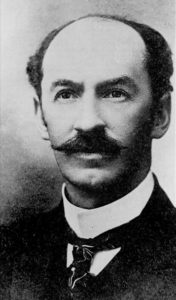

The report also recommended the creation of the position of director of education. The man appointed to that position, Frank Tate, was not a person likely to be satisfied with the restrictions listed above. His early writings revealed his belief that, if the state was to progress, its general population needed to be educated, not just those with enough assets to attend private schools. And that education should be a general one, designed to create urbane, rationally-thinking individuals, rather than technicians with skills and knowledge confined to narrow specialties.

Frank Tate, unknown photographer, Federation University Historical Collection (Geoffrey Blainey Research Centre)

But how to do it, considering the limitations set by the royal commission? Tate may have been an educational idealist, but he was also a political realist. He was determined to manipulate the legislation as much as he could. Establishing Melbourne Continuation School was not a real problem. The state needed teachers if it was to expand its activities into post-primary education, and the school was ostensibly created to train junior teachers through a general education course. However, there was no compunction for the students to become junior teachers. They could, if they so wished, move on to senior classes and undertake courses designed to facilitate university entrance. Many of them did. Tate’s first move indicated clearly the educational direction that he wanted to take.

However, his argument about junior teachers would not wash in regard to the rest of the state. Now he became the political realist. The parliament also contained a sizeable number of rural representatives, many of them keen to see schools established in their districts. He found that the rural members had the political power to grant money for the establishment of such schools in a few locations. However, those schools had to be of a technical nature, in line with the royal commission’s recommendations and reflecting the influence of the private schools lobby. A scheme was devised in 1905. The government could use a grant of three thousand pounds to establish agricultural high schools under the following conditions: at least one-half of the cost of the necessary buildings and equipment was to be contributed by the local community and an area of land at least twenty acres in size provided for the school’s farm (which would be expected to become self-supporting). Over the next few years, in addition to those at Sale and Warrnambool, such schools were established at Shepparton, Wangaratta, Leongatha, Mansfield, Warragul and Colac . A continuation school established at Ballarat in 1907 became an agricultural one in 1910. A continuation school established in Bendigo at the same time was originally planned to be an agricultural one but some sleight of hand led to it remaining as a continuation and then a high school.

This is where Tate created a subterfuge. Yes, the schools did offer a course in agriculture, and some students opted for it. However, it was poorly devised, often poorly staffed, poorly resourced, only offered at forms three and four level and led nowhere. The students did not even receive a certificate of completion. In a number of cases, the land offered for the farm was generally unsuitable for the activities that were supposed to be carried out there. Of more importance, right from the start, was the continuation course that Tate added to each of the schools. It was the same course as that offered in Melbourne, and it put the schools in direct competition with local private institutions. As an example, the Wangaratta school, which opened with nineteen students on 20 April 1909, offered its continuation course for the fee of one pound ten shillings per quarter (the agricultural course cost two pounds two shillings per quarter). The fees at the local grammar school would have been much higher. The high school also enrolled girls and had a uniform to enhance its prestige. We can see both in the Mt. Morgan photograph.

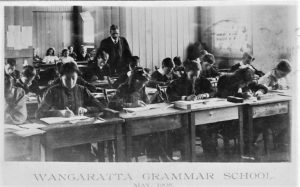

Wangaratta Grammar School, May 1908.

The headmaster of the Wangaratta Grammar School, Mr. J. W. Thomson, who had opened a ‘spacious new college’ in 1907, was quick to see the effect the new high school was likely to have on his enrolments. At his institution’s speech night in December 1908, before the high school had even opened its doors, he stated:

How is the Grammar School going to get on when the Agricultural High School with its so-called Continuation classes is opened? In other towns under the same conditions, the private schools have been closed. I find it very hard to say what effect the new school will have on us in the future, but if it is going to do us harm, we are not going to give in without a fight. (Wangaratta Chronicle, 19 December 1908)

At the same gathering a year later, perhaps with a tinge of bitterness and despair, Thomson indirectly indicated what effect the high school was having when he commented that: The state is now entering boldly into the realms of secondary education pure and simple, although they still call their Secondary School Agricultural, and pretend that all other pupils are being trained for teachers. (Wangaratta Chronicle 18 December 1909)

The die was obviously cast. Only six months later, the Chronicle recorded that Thomson would probably be on the staff of the agricultural high school in a temporary position from the start of the coming term. The grammar school would be continued under other management. However, it is doubtful whether it did, for no speech night report was published for it in that or any future year. Thomson, no doubt sadly defeated, had obviously adopted the motto of, ‘if you can’t beat them, join them.’ He stayed at the agricultural high school for a number of years and, after a period at Warrnambool, he returned to become – the supreme irony – the headmaster of the school in 1919. The fate of the grammar school is not an indication that the local population was crying out for a government institution. In the case of almost every agricultural high school, the stated requirement that the locals contribute half of the cost of the buildings was not met.

Wangaratta High School, unknown photographer, allegedly cir 1910. The decrepit fence and well grown hedge suggest a later date, unless they are remnants of when this block was used by the State School.

In 1912, Wangaratta’s contribution was listed as being five hundred pounds – only one-third of the amount required by legislation. Still, the government went ahead and established the schools. Enrolments, as we can see from the photograph, were not pouring in the doors. One reason for this is the fact that, in the beginning, many people did not realise that the schools offered both an agricultural course and a continuation one. In early 1909, at a public meeting held at the Theatre Royal to discuss the establishment of the school was adjourned because of the small attendance. Only twenty-five people bothered to turn up, despite the fact that the creation of the school had been mooted since the announcement of the government grant in 1905. The lack of understanding of the school’s purpose extended as far as 1911 and probably beyond. In 1909, Headmaster Schilling lamented that he had sent 100 appeals to the heads of district primary schools, informing them of the school’s existence and purpose, but had only received two replies. Worse still, in December of that year he informed the education department that three students from the Rutherglen State School were going to the Melbourne school instead of Wangaratta the following year. Schilling recognised the problem in a comment published in the Chronicle two months later when he wrote:

Many parents have conceived the idea that only agricultural subjects are taught at the school, but such is not the case, as a continuation school is also provided, and the same subjects are taught as at the Melbourne Continuation School. (Wangaratta Chronicle 12 February 1910)

None of the schools started with the legally required local contribution and none of them started with the legally stipulated fifty agricultural students. Tate was prepared to skirt the regulations to get the schools off the ground. Initial agricultural enrolments, while less than those of continuation students, were heartening. At Warrnambool in 1908-9, for example, thirty-five to forty percent of the enrolments were for the agricultural course. However, as time went on and as the education department consistently failed to provide funding for suitably trained staff and adequate facilities, the numbers declined, while those for the continuation courses increased. Moreover, the quality of the students studying agriculture became an issue. As Schilling’s successor, F. C. Refshauge, wrote to the department in 1914:

There are fifteen junior students taking the Agricultural Course; some of these are but 13 years of age, and the most of them are very backward in their work. They require special attention, especially if the Agricultural side of the school is to be kept to the fore. (Departmental Correspondence, Wangaratta High School, 18 February 1914)

Nothing was probably done about this however and, by 1916, the school was reporting no students doing the agricultural course. In the same year, the word ‘Agricultural’ was semi-officially deleted from the school’s title. It was never to return. The fate of the other agricultural high schools was similar. By 1917, they were all classed as district high schools. Frank Tate had succeeded in his purpose and has the right to be described as the father of the modern government school system in Victoria.

As for the school farm, it never made its way. Local historian D. M. Whittaker writing in 1963, noted that

Despite its early praise the farm did not prosper. Frequent changes in the position of farm manager, the impossibility of running a 20-acre farm at a profit, and the dwindling number of students taking the agricultural course resulted in the farm ceasing to to be of practical importance in 1916.

Just how many of the students in the Mt. Morgan photograph were undertaking the agricultural course we do not know. One can only suggest that, as the course began at year nine level, some of the younger-looking children were probably involved. Older ones were probably enrolled in the continuation course. This group of students came from a fairly wide area in north-eastern Victoria. The enrolment register for 1909 lists the following locations: Stanley, Rutherglen,Great Southern, Tallangatta, Porepunkah, Violet Town, Benalla, Hansonville, Milawa, Eldorado, Docker’s Plains, Taminick, Oxley, Moyhu, Greta, Londrigan and Wodonga and, of course, Wangaratta itself. Just what happened to each student once he or she finished the course is difficult to discover. However, an honour roll in the possession of the school records that the overwhelming proportion of this first intake were junior teachers by 1914. Other occupations included a coachbuilder, a mechanic in the Newport Railway Workshops, a public servant and a bank teller. The fortunes of many were represented by A. E. Warnock, who entered the school in 1909 and undertook the agricultural course, but ended up by becoming a clerk in the titles office in Melbourne. It was only after service in the First World War that he returned to the land at Winton, possibly as a soldier-settler.

Wangaratta Agricultural High School students, December 1909, by J E B Archibald, Albury City Museum ARM 84.114

And as we look again at the photo, we can wonder what happened to most of the students in their after-years. Being born in the depression years of the 1890s, how many had already suffered deprivation in their early days? How many of the boys or teachers enlisted in the armed forces at the outbreak of World War One, or later? Did any of them die on the hills of Gallipoli, the sands of the Sinai and Palestine or the trenches and battlefields of the Western Front?* Did any receive grievous wounds, mental or physical, that incapacitated them for the rest of their lives? How many of the girls became nurses during the war or worked in war-oriented industries? How many of them married and had children, and possibly lost sons in the next war? The questions that arise are endless.

For the time being, let them enjoy their picnic, their climb up the mountain and the evening meal they enjoyed after returning to the school. The whole image is timeless. Their faces reach out to us across the space of 110 years. Let us also be grateful to the photographer who ascended the mountain with them to leave us with this magnificent picture. James Emile Bredenberg Archibald was a member of a well-known Wangaratta family. His father in 1909 was a miller at Teague Brothers Victoria Flour Mills in the town. It is interesting to note that James, born in December 1894 in Melbourne, had just turned fifteen at the time he took the photograph. So, logic has it that he was a student at the school. James had a varied life. He was obviously a keen observer, writing descriptions of his adventures to the Leader newspaper as early as 1908. After leaving school, he joined the army in 1916 and went to the Western Front. He trained as a gunner, and then a signaller and was involved in action until taking ill with pyrexia (fever) in September 1918. On his return to Australia in early 1919, he followed his father into the flour milling trade at Smeaton, near Ballarat.

Smeaton Mill by John T Collins 1907-2001, State Library Victoria

By 1921, Archibald was back in the north-east, working as a farmer on a soldier settlement block at Hansonville. Perhaps this was not a successful venture (many of them were not, owing either to the poor quality of the land provided, or the lack of farming skills among the ex-soldiers, or both) as he is recorded as spending his later years as a miller, working in Footscray North. He died in 1961 at the age of sixty-seven.

*At the school speech night in December 1916, the acting headmaster reported that sixty-three former students had enlisted, nine had paid the supreme sacrifice, three were missing or taken prisoner, and six were wounded. Earlier that year, Australian soldiers had participated in the horrific battles of Fromelles and Pozières/Mouquet Farm. (Wangaratta Chronicle, 23 December 1916)

If the reader is interested in gaining a fuller perspective of the role of the agricultural high schools in the development of secondary education in Victoria, my 1977 thesis on the subject can be accessed and downloaded online. Google ‘The Victorian agricultural high schools’ or see this link.

* Mt Morgan is the previous name for Mt Glenrowan. It was named after the bushranger ‘Mad’ Dan Morgan who had a lookout there. It is believed that the excursion may have climbed to the lookout.

** Thanks to Sarah at Albury Council Museum and Social History Collection who happily answered my questions about the Archibald image and scanned both the image and the rear of the image to assist in identification. Our collaboration will make the catalogue entry for this item more accurate, and will help with another post about this young photographer ¬ Jenny Coates.

I have a postcard entitled “A.H. School Farm Wangaratta”, photo by A.J. Evans

Hi Graham,

That’s interesting! I have a scan of one with boys ploughing but it is very small and of poor quality. Is yours different do you think?

Kind regards,

Jen

I was pleased to see this article on Wangaratta High School and the mention of John William Thomson.

As I am doing research on John Thomson as he was principal at Hamilton Academy in Hamilton ,Victoria from about 1894 to 1900.

To date we have very little on his life and I wonder what more information you may be to provide. Do have a photo of John Thomson?

Ian Black

Thanks for dropping by Ian. If you’d like to use the contact form to send me your email address I’ll pass your query on to Rod Martin.