Ada Cambridge, as we have seen in previous posts in this series, enjoyed an active social life.

There were bazaars and church teas and such things – quite as exciting as the private functions – at which our circle of friends and acquaintances was augmented by the leading tradesfolk, between whose class and that conventionally supposed to be above them the line of demarcation is always very thin, sometimes scarcely perceptible – and properly so, in these isolated communities.

Ada was commenting on a phenomenon that the author has noticed in the early development of Wangaratta at least up until the 1870s. Many townsfolk had the egalitarian view that it was only through co-operation and diversity that the town would grow and prosper. Hence, people like my ancestor William Henry Clark assisted in almost every innovation and new association or club in the town. They were also very supportive of different religions and churches. Clark, a staunch Anglican was noticed supporting St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church. He had personal and business associations with many on the other side of the Catholic/Protestant divide, including people like Michael Cusack, a fellow publican and first Councillor of the borough. Despite being a large landowner, and a town innovator Clark was looked down on by some of the squatting aristocracy as not being of the same sophisticated class as themselves. It seems that for some, inherited old money and self made money was the divide, but this is not reflected in Ada’s attitude, nor in the attitude of many ordinary townsfolk.

I keep in affectionate remembrance the wife of a stationer who was like a mother to me, the wife of a general storekeeper who often sat with me when I was lonely and needed looking after …

The stationer’s wife that Ada mentions was Anne Bickerton. Born as Ann McCallum in Rothesay, Bute in 1834, Anne was the epitome of resilience and fortitude. She had married Hugh Munro, a fellow Scot at the Wangaratta Anglican Trinity Church in 1857, although both said they were members of the Free Church of Scotland. Both were living at the gold settlement of Woolshed, with Hugh recording himself as a merchant. The couple had three children, the last, Dugald born in Wangaratta in 1861. Around this time Hugh Munro became a book seller and stationer and he was also one of the first borough Councillors and a cemetery trustee. His untimely death at the age of 31 in March 1864 left Anne all his assets including the small business. Undaunted, and despite having three young children, Ann took over the reins of the business and immediately made it her own.

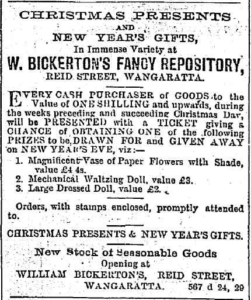

In September 1868 Anne Munro (nee McCallum) married Town Clerk, insurance agent and bachelor William Bickerton. With this simple act, she was relegated from the title of independent businesswoman to the anonymity of ‘a wife’. Her business was now under the name and auspices of her new husband, although I could easily believe that Anne remained a leading force in the business.

Ovens & Murray Advertiser, 20 December 1870, p 3.

Ada Cambridge’s memories of Anne Bickerton as mother-like is interesting. Anne was only 11 years older than Ada but her life experience probably contributed to her endearing nature. Anne lost her second child and oldest son in 1865 during her widowhood. She had a fourth child with second husband William Bickerton in 1869 so was a contemporary, but more mature mother to Ada. As such she may have assisted Ada as she entered motherhood for the first time, and far away from her own kin.

The “the wife of a general storekeeper who often sat with me when I was lonely …” was most likely Welsh born Mary Sarah Thomas (nee Hughes). There were many other candidates who were the wives of well known and relatively wealthy storekeepers, such as Maria Francilla Dixon (wife of James, who in 1870 was the Mayor of Wangaratta), Marianne Gibson (Presbyterian), Jane Lucas (husband Edward was a witness to the Will of Hugh Munro – above), and Maria Louisa Willis whose husband William was the Mayor of Wangaratta 1868-1869.

Mary Sarah Thomas, however, had an extra close connection back to Ada Cambridge’s social circle. Her husband John Hampden Thomas was the informant at the death of Dr James Hester (whom we met in Part 3 of this series), recording his relationship as “friend”. The doctor present at the birth of Mary’s first child Arthur Henry Thomas on 2nd December 1870 in Reid Street, was none other than James Hester, and his wife Jane Caroline Hester (nee Churchill) was recorded as a witness to the birth. And if any further evidence of a connection is needed, John Hampden Thomas, acting as secretary in April 1870, called for tenders for additions to the Trinity Church parsonage.

In Part 6 of this series we will meet another exceptional woman who inhabited Ada Cambridge’s social circle – qualified chemist Sarah Rundle (nee Bulmer).

**All quotes from Ada Cambridge in this series of posts are from Thirty Years in Australia, available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b566133. This post refers to page 40.