Following on from the last Trove Tuesday we continue reading an account of Wangaratta published in the Ovens & Murray Advertiser (O&MA) in January 1863.

As in all Australian cities, the public-houses of Wangaratta are a prominent institution, six in number; two of them well merit the title, ‘Hotel,’ arrogated by five—offering good accommodation for man and beast, and equal to any Colonial inns for comfort and respectability. The Horse and Jockey Inn is noted as the favored resort of those sporting men who, wishing to combine ‘ the comforts of a home’ (vide prospectus of Minerva House Academy) with the privacy requisite for training arrangements, look on it as rus in urbe•

It is not clear if the author meant Wangaratta had six hotels or seven in 1863. Nor does he mention the second establishment he considered worthy of the name ‘hotel’ so it is also difficult to know which he considered “arrogated” themselves. The hotels known to be in existence in January 1863 were:

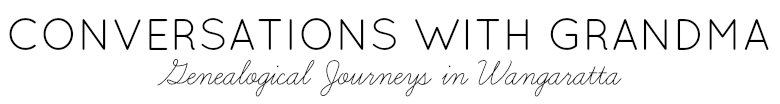

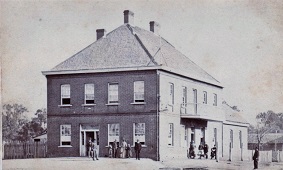

- The Horse and Jockey on the corner of Ryley and Warby streets (and still known as the Horse and Jockey corner) was licensed to James Blake in August 1859 when he made headlines by refusing entry to a seriously injured man. Dr Dobbyn requested that Mr. J. Connelly, who had been thrown from his horse and suffered a compound fracture of his thigh, be admitted for treatment. Blake was charged with an infringement of the Licensed Victuallers Act by refusing to admit a traveller. Magistrate Shadforth stated that he “should have expected very different conduct from an old publican”, suggesting that Blake had been in the establishment for some years. The Horse and Jockey Hotel first received mention in the press in February 1859 in relation to an annual three day horse racing carnival. The large advertisement mentioned four hotels, each of whom were evidently selected to share equally in the spoils of a large number of people who would retire there after long days of revelry at the horse track. The four hotels mentioned in the advertisement were the Horse and Jockey, the Royal, the Australian and the Commercial.

Horse and Jockey Hotel from D. M. Whittaker’s book.

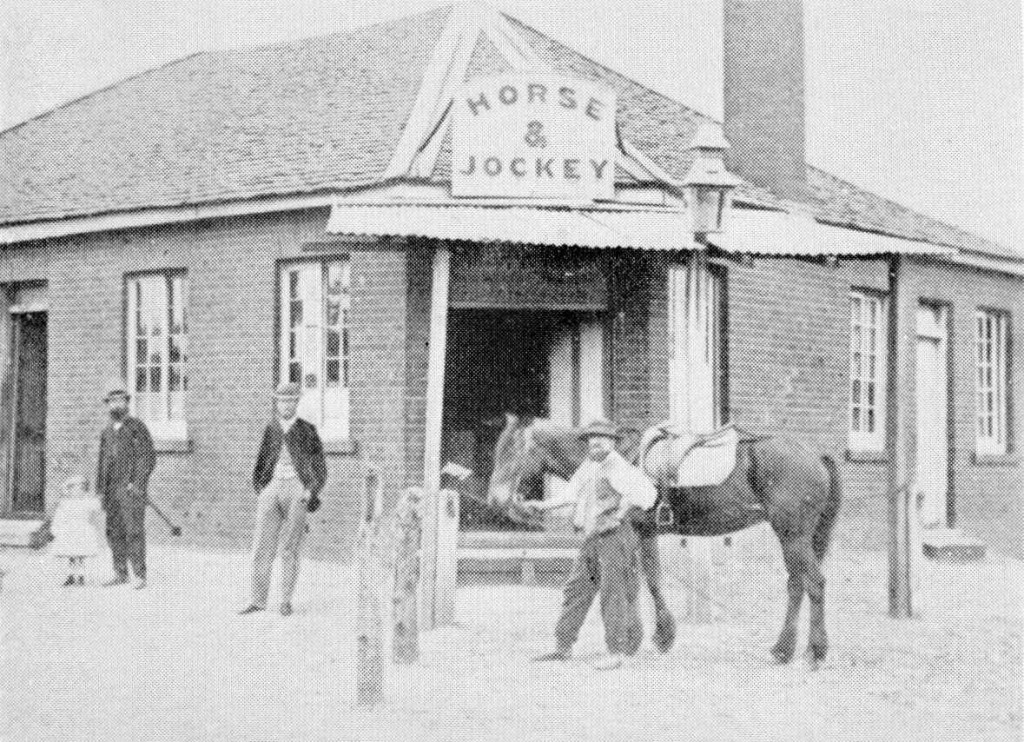

- The Royal Hotel in Reid Street operated from as early as 1852, and most probably before that time. It became the Pinsent Hotel when Annie Edith Pinsent, the licensee since at least 1917, purchased the freehold and changed the name from the 1st January 1923. Later the hotel was run by Annie’s son Arthur Henry. Licensed to John Crisp in 1852 the Royal Hotel had passed through several hands until 1863 when Thomas Cusack (son of Michael Cusack who was also the secretary of the Annual Race Meeting) owned it, and the next year when Henry Kett was the licensee.

Pinsent Hotel advertising card circa 1930s

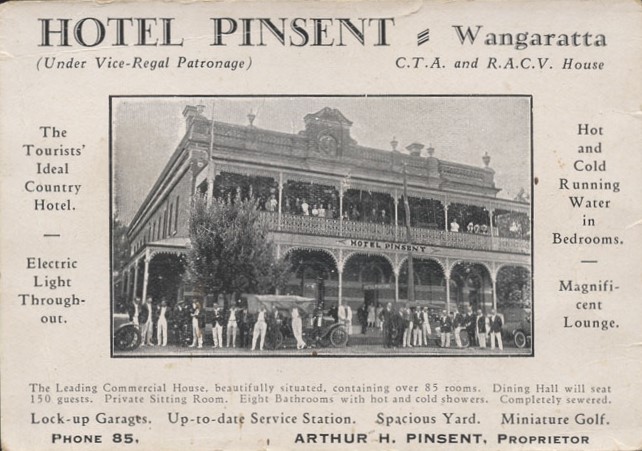

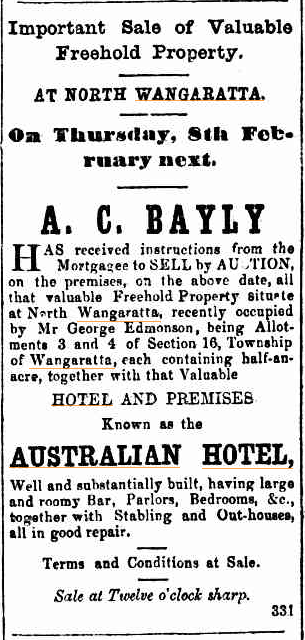

- The Australian Hotel on Parfitt Road was licensed to Samuel Evans as early as September 1858 when it hit the news as the location of a mass poisoning of dogs. By July 1864 the Australian had been taken over by George Edmondson (recorded as Edmonston) whom we met in a the previous Trove Tuesday post when he commenced a brewery at the hotel. The brewery having failed, Edmondson put the hotel up for sale in February 1866. The hotel was de-licensed in 1912 when Mrs Isabella Dale was the owner and licensee.

Australian Hotel, sale notice February 1866

- The Commercial Hotel, earlier the Commercial Inn, was owned by William Henry Clark from at least January 1855 until his death in April 1871. Owning dozens of blocks all over the town, Clark was probably hedging his bets by building on Murphy Street a far more impressive hotel than the defunct and destroyed Hope Inn ever was. By June 1861 Clark had transferred the license of the Commercial to William Murdoch, preferring to retire to his pre-emptive selection on the outskirts of town, but he had resumed the license by 1870.

Commercial Hotel circa early 1860s. The veranda was added by William Murdoch in the 1870s.

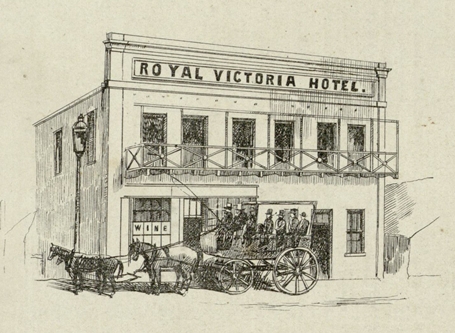

- The Royal Victoria Hotel in Faithfull Street, on the block to the west of the Court House, was described in 1857 as “betwixt the new bridge and the punt”. It was built by Thomas Millard in early 1855 for between £7,000 and £8,000. The bricklayer was my relative Christopher Cook who built the Wangaratta Steam Flour Mill. The Royal Victoria was sold in March 1858 at Millard’s insolvent estate sale to Andrew Stark who still owned it in 1863. The hotel was given an art deco renovation in the 1930s in keeping with the court house style but was demolished recently to make way for a truly ugly and soul-less Centrelink office. It is a shame the Wangaratta Council doesn’t place any priority on preserving streetscapes as this was a rare art deco combination and one of Wangaratta’s oldest extant buildings.

Royal Victoria Hotel, 1857

- James Meldrum’s Wangaratta Hotel which stood in what is now Clements Street (or possibly facing Bickerton Street) was mentioned in newspapers in April 1852 when locals were attempting to talk up gold prospecting near the town. Thomas Millard assured readers that gold was there for the taking conveniently just behind his Wangaratta Store. James Meldrum was quite happy to let readers know that he was purchasing gold taken from behind his friend Millard’s store and from parties prospecting at Reid’s Creek. Positioned, just like many of the inns, to take advantage of travellers stopping to cross the Ovens River using Clark’s punt, Meldrum’s hotel stood in direct opposition to Clark’s Hope Inn on the north bank of the Ovens. Whittaker noted that the establishment began life as Bond’s store and inn. He claimed this was John Bond but ownership at this time is unclear. The Inn was also the location of the Post Office which was established in 1843 and each subsequent owner became the Postmaster. John Dunmore Lang reported staying at the inn in January 1846. In July 1846 William Carpenter Bond transferred the license to John Rogers. James Meldrum took over in 1847 and built the Wangaratta Hotel. For a short time in 1855 Meldrum transferred the license of the Wangaratta Hotel to a Mr Rogers (possibly the former owner) but retained ownership, probably while he took a trip back home to show off his huge wealth. James Meldrum died on the 15th February 1865 at the young age of 47, followed by his only daughter Margaret in December 1866. Meldrum’s widow Mary (nee Leacy) sold up and returned to Ireland. The lure of the hotel must have been strong as Mary returned to the town and again purchased the Wangaratta Hotel, operating it until around 1888. She died there in 1896.

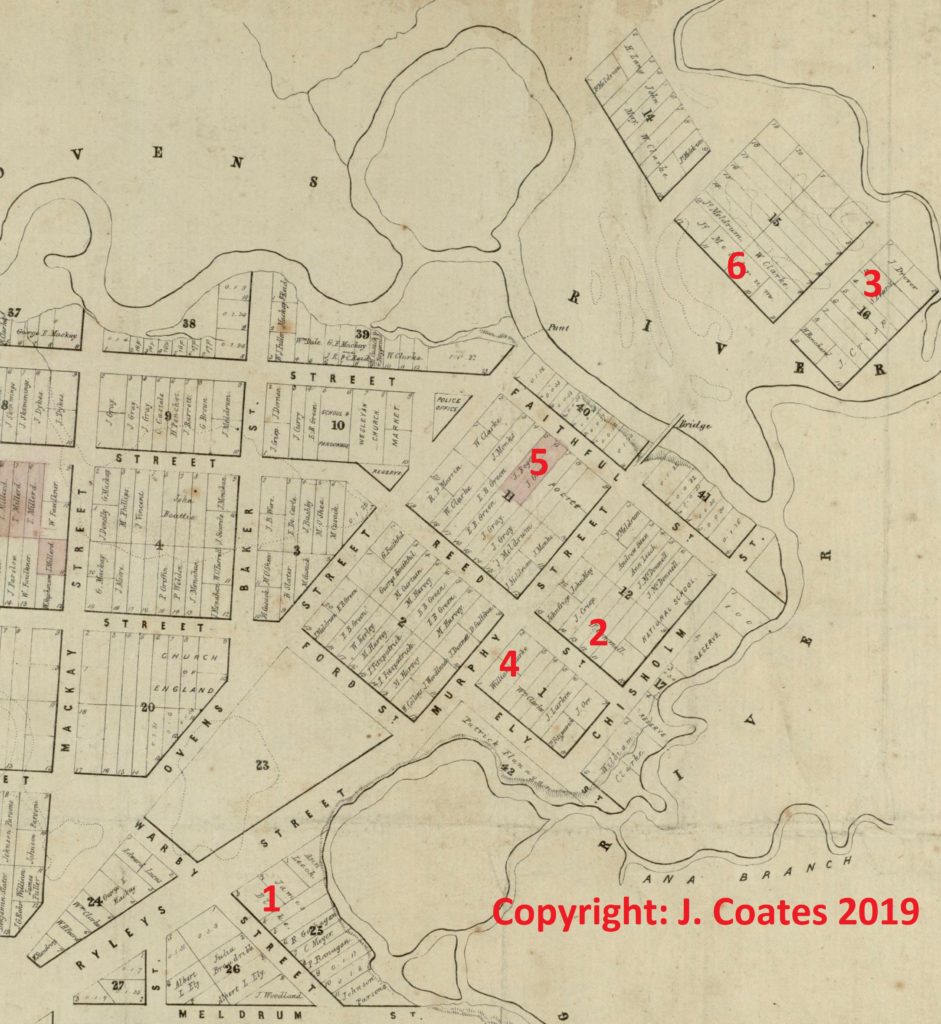

Wangaratta hotel locations as at January 1863

Apart from the Horse and Jockey which positioned itself on the outskirts of town, possibly near an early racecourse, most of the early hotels vied for position around the Ovens River. The intention was to catch the passing trade of travellers between Sydney and Melbourne, and diggers heading to the Beechworth goldfields. All had to stop to consider how they would cross the river – by punt or (by the late 1850s) the toll bridge between Murphy Street and what later became Parfitt Road. This positioning was before the mid 1850s a complete gamble as it wasn’t known if Ovens Street or Murphy Street was going to be selected for the location of a bridge. Every publican hoped that the bridge would be built closer to their establishment than a rival’s, and that the street they were located on would become the main thoroughfare. At first everything centred around Clark’s Hope Inn and his punt, but when the toll bridge was built along the line of Murphy Street and Parfitt Road, the dynamics of the town center changed with a shift towards Murphy Street as the main thoroughfare.

Hello, i am quite possibly related to the samual evans who had the australian hotel, im wondering if there is any other information or even photos of him available, thanks

Hi Francine,

Samuel Evans who had the Australian Hotel from the late 1850s to early 1860s was born in NSW and had two marriages, firstly to Mary Ann Newton and secondly to Mary Hoy. Does this sound like your Samuel?